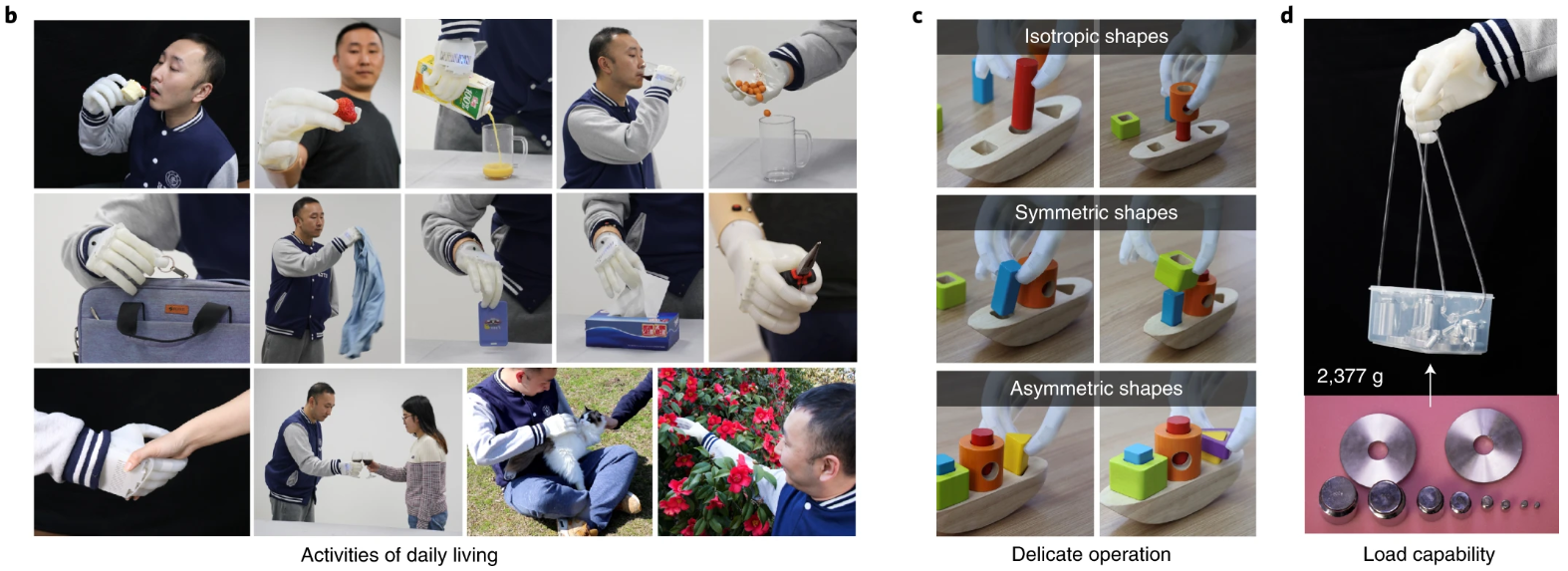

Recent innovations in active prosthetics have significantly improved the rehabilitation of amputees into normal society, increasing the capability of performing activities of daily living (ADL). However, the inherent limitations of traditional prostheses call for the adoption of soft robotic technologies to better bridge the biomimetic gap towards natural human anatomy. This review examines ongoing research within the domain of soft robotic prosthetics, focussing on highlighting the various factors involved in the design and development of these devices, while also speculating on upcoming breakthroughs and their potential broader impacts.

Among the many physical advantages humans possess, the ability to touch and dexterously manipulate objects in the environment in the way we do is a core component of the human experience. This makes restoring such functions even more important when we lose limbs to injury or disease, and the advent of artificial limbs has helped us significantly in that regard. However, while we have been successful to an extent in restoring lost motor functions to assist with Activities for Daily Living (ADL), this has come at the expense of burgeoning costs and complexity in mechanism design, further compounded by the lack of small-scale sensors that can provide intelligent feedback about the environment through the prosthetic to the wearer. These issues arise from the limitations imposed by conventional materials in integrating electronics and sensors as well as other size, weight, power, and cost (SWaP-C) restrictions. Soft robotics thus emerges as a likely solution to the restrictions of design and functionality imposed by traditional materials.

Soft robotics is a rapidly developing field primarily characterized by the use of soft materials and sensors in the construction of robots. The two defining advantages that soft materials posses over traditional materials are:

- Compliance: Low stiffness allows soft material matrices to conform to the shape of rigid objects and be flexible to external forces. This allows for soft robotic mechanisms to be naturally compliant or stiff depending on the situation or method of actuation.

- Embeddability: Unlike a block of steel, a block of silicone can have objects embedded within the bulk of the material. This opens up possibilities to embed sensors and electronics, thus allowing for ‘denser’ designs within the same volume or area.

These two properties lend itself greatly towards the development of soft robots, especially since most typical applications of soft robotics in the literature take after biological organisms1. This helps make a stronger case for the inclusion of these modalities in the field of prosthetics, which as of now has only just been able to start escalating research technologies towards commercially-available levels of technical readiness.

In this review, I begin by laying out the current landscape of prosthetics research; identifying active areas of research within the taxonomy; and finally discussing works in the literature that have addressed those areas, either directly or indirectly. Due to the lack of literature surrounding soft robotic prostheses specifically I shall extrapolate from existing medical literature around traditional prostheses and soft robotics literature. Most of my review is tailored towards upper-limb prosthetics (ULP) and anthropomorphic hands, although I include minor references to advances in lower-limb prosthetics (LLP), due to the relative abundance of work in ULP technologies that soft robotics can easily adapt to.

System Taxonomy

On a high level, the prosthetics literature divides a typical prosthesis into two main categories: its mechatronics, namely the combination of the mechanical and electronic components necessary for its operation, and the control strategies and algorithms implemented to orchestrate its functions. I break this down further into the following sections, while also adding additional context from medical literature:

- Amputations and Human Factors: Amputation site and the impacts on ADL greatly drive the scope of application for current prosthetic technology. Most work in this field is relevant to the medical literature, so my review will be restricted to an overview of its impacts on the other subsystems.

- Signals and Systems: Consisting of input control systems and sensory feedback, this subsystem covers advancements in EMG and neural control, as well as sensors currently being developed for prosthetics and anthropomorphic hands. My review of this subsystem will draw greatly from the medical literature, highlighting relevant examples from work in soft robotics that may be translatable to this area.

- Design and Actuation: Consisting of design methods and materials used in the development of prosthetic devices, this subsystem may see the most impact from advancements in soft robotics literature. Therefore, my review will draw greatly from existing reviews of wearable haptics, intelligent materials and compliant mechanisms in the soft robotics literature to highlight their potential applications in prosthetics.

Amputations and Human Factors

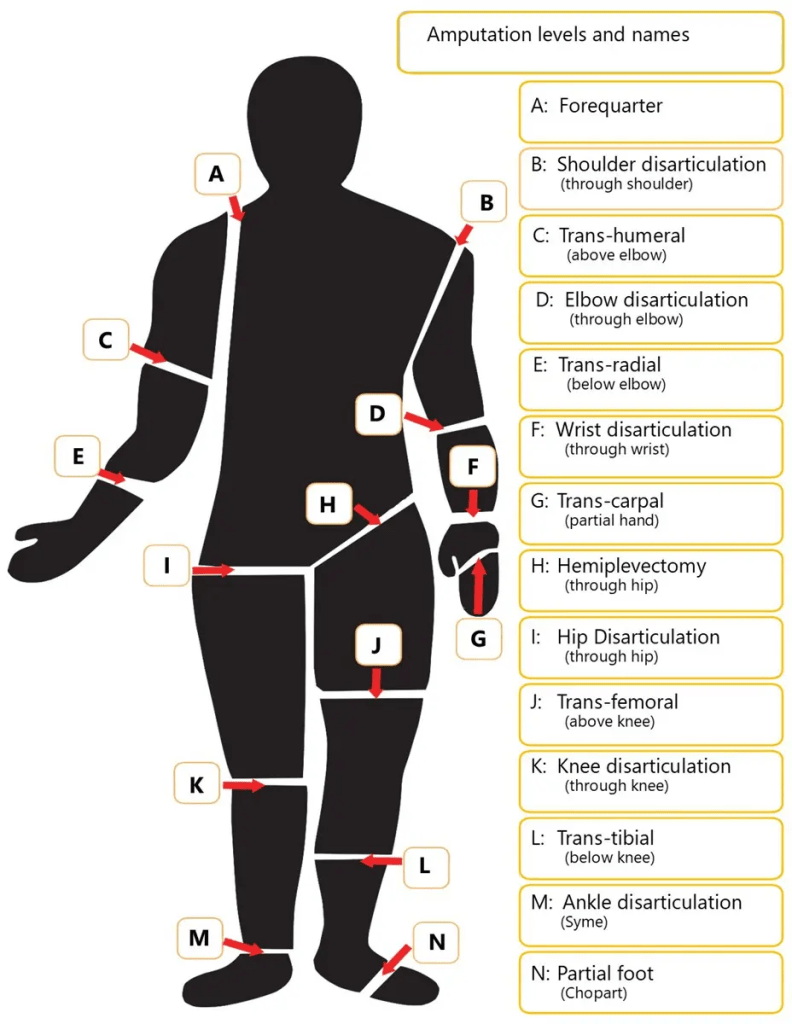

The scope of prosthetics is primarily driven by advances in medicine and surgery as opposed to engineering. Contributing factors during the initial assessment of the patient, the surgery undergone, and response to rehabilitation greatly determine the type of prosthesis and its efficacy3. Different sites of amputation can affect the scope of prosthesis design—a trans-radial amputation will have different impacts on patient ADL and prosthesis constraints compared to a trans-humeral amputation.

Prostheses can also be passive (purely for cosmetic reasons or limb supports in the case of LLPs), or active with actuators and sensors to restore motor function. The degrees of freedom impacted by the amputation restrict the motor function available to the amputee which cannot be substituted by any passive prosthetic, however, and thus most recent work in the literature is now focussed around active prosthetics for upper and lower limbs instead. The greater the amputation, the larger and more complex the prosthetic, which further places constraints on SWAP-C limits, as so most research is focusses on optimizing systems and mechanisms or using lighter materials to achieve the same4. Overall, there are many extrinsic and intrinsic factors, that influence clinical use of prosthetics technology and function.

Signals and Systems

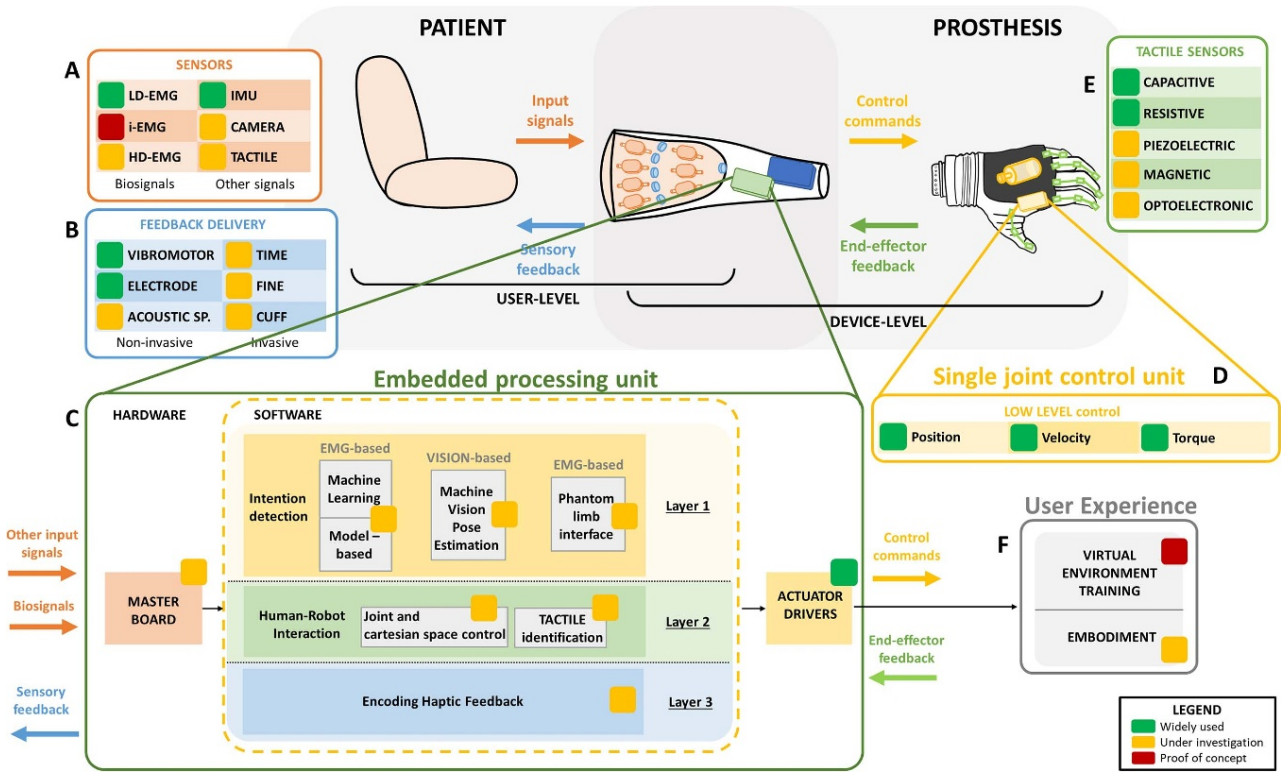

This system architecture for both ULPs and LLPs is similar, with the inclusion of an additional autonomous processing component on ULPs because of their heavy reliance on user intent for daily operation in contrast to lower limb prostheses that can be operated using autonomously gait algorithms. This subsystem can be thought of as a closed-loop control system containing two parts:

Input Signals

Input signals include all the sources of information that can be taken from the amputee and translated into motor commands for driving the prosthesis. The most prominent methodologies involve tracking biosignals, signals collected from the activity of different tissues or organs belonging to the human body. Control strategies currently used in prosthetic applications have not changed since their first appearance in the 1960s, still relying on electromyography (EMGs) to detect electrical signals originating from muscle fibres in the amputation stump, but new research involved brain signals has ushered in a new field of neuroprosthetics, where brain activity is mapped to control inputs.

Sensing and Feedback

Sensing and feedback information encompasses different prosthetic sensing solutions acquired either from the prosthetic device or from the environment that can be translated into sensory stimuli for the amputee. Natural movements occur with a bidirectional flow of neural information, i.e. motor commands on one direction and sensory feedback on the other, and thus, establishing a good closed loop relying on embedded sensors within the distal regions of the device in contact with the environment is critical. This is an active area of research in the soft robotics literature, where intelligent soft materials and sensors have been adapted to prosthetic-like form factors5.

Design and Actuation

Regardless of the type of control system, the most critical aspect of a prosthetic as a mechatronics device is the degrees of freedom that can be actuated through those control signals. While most traditional prosthetics are built out of rigid materials like aluminium and carbon fibre, which, while being light and robust, lack embeddability—this restricts the available volume within which the sensing and control equipment described previously can be fit within. Aside from the materials used, the mechanisms that can be accommodated within the design volume also contribute greatly to the mechanical functionality of the device as a whole. This subsystem is divided into the following aspects:

- Materials: As stated previously, the limitation of traditional rigid materials indicate a gap in the field that can be filled by work in soft robotics and intelligent materials, specially in wearable haptics and proposed robotic skins for prosthetics. 3D-Printing is also an emerging field that has been examined in the prosthetics literature as an effective low-cost alternative material6.

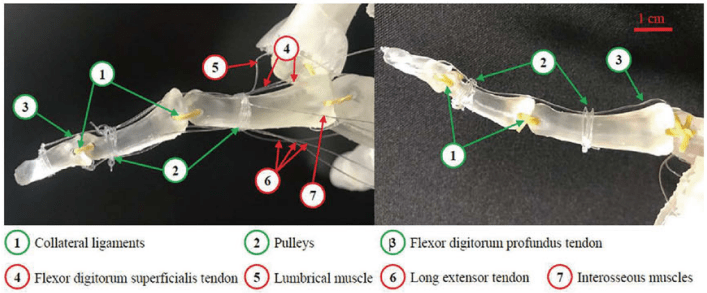

- Design and Mechanisms: Given the need for mimicking natural human movement, the rise of biomimetic design in the soft robotics literature also reveals work in the design of soft anthropomorphic hands, leveraging the inherent compliance and embeddability of soft materials7.

Emerging Trends

Prosthetics and soft robotics literature appear to agree on the limitations of current prosthetics and the benefits of soft robotics in those areas. This has lead to the rise of ‘soft prosthetics’11, a convergent field of research blending the modalities of prosthetics and replacing certain components in the process with existing innovations in soft robotics. Multiple works adapt traditional soft robotics principles to the field, addressing sensing, intelligent materials12, and design13. This section covers certain works in the field that I felt best exemplified the ideas I wished to highlight and elaborates on how these advancements may be adapted to prosthetics.

Intelligent Materials and Soft Sensing

Hegde et. al. and Zhu et. al. review different soft sensors and robotic materials for various soft robotic applications. Sensors with ‘flat’ and ‘tip’ profiles are preferred for our usecase, particularly flex strain sensors and capacitive/impedance-based touch sensors that help with proprioception and tactile perception and characterization. One particular example uses optical waveguides for tactile perception and proprioception embedded within a soft anthropomorphic hand. While the hand itself is pneumatically actutated, the small form factor and embeddability of the sensor within the curve of the fingers itself positions itself as a good solution for creating more space-efficient designs within the same volume. Such examples, alongside more well-known examples of 3D-printed prosthetics and soft robots signify a great lowering of the barrier for the types of materials and manufacturing techniques in the creation of soft robots.

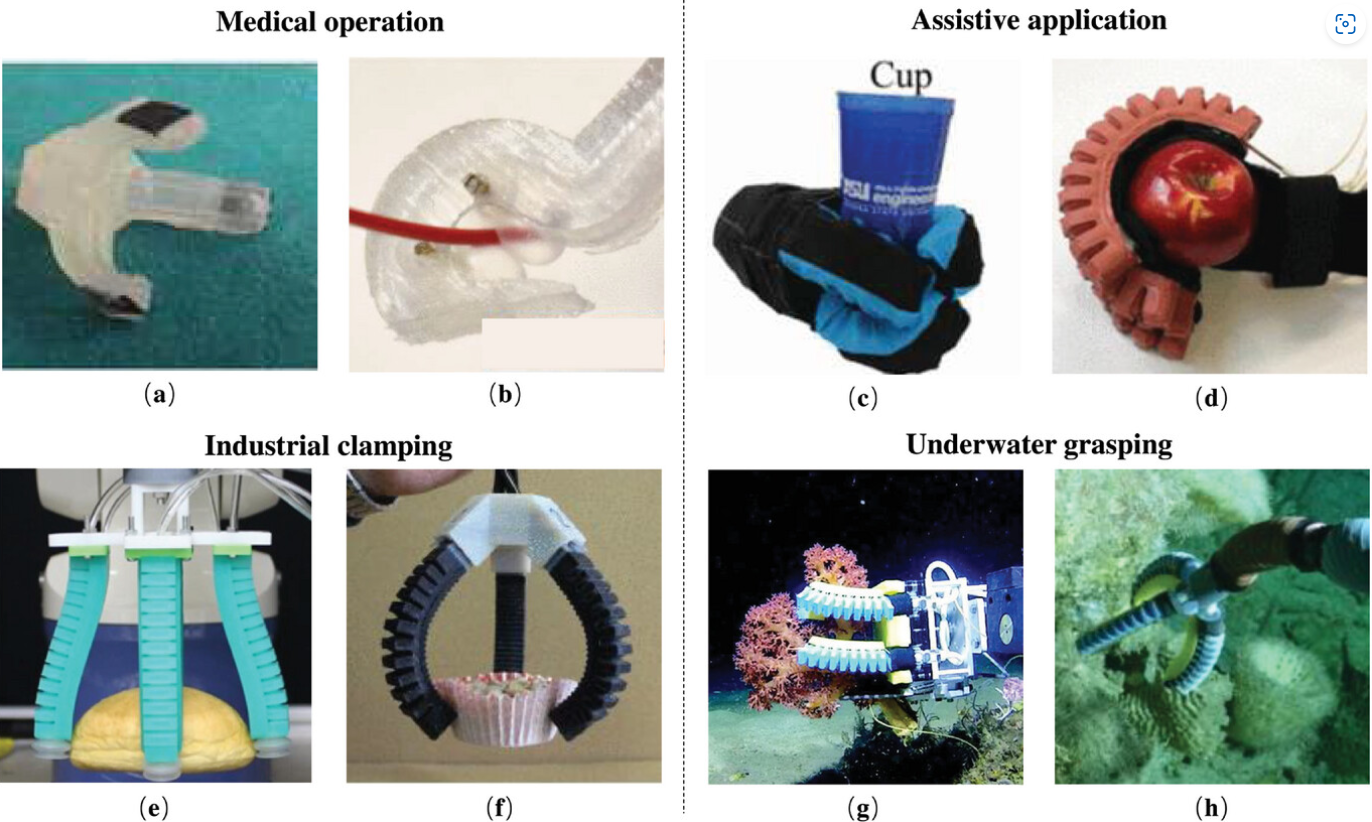

Design and Fabrication

Shan et. al. describe different designs for grippers that incorporate principles similar to what I believe can be applied in the design of prosthetics. This is most exemplified by the work of Gu et. al., which to my knowledge is the most complete attempt at the idea of a bonafide soft neuroprosthetic. The device utilized a PneuNet-based finger design system, similar to typical soft grippers, with embedded touch sensors to provide tactile feedback to the wearer. The overall design of the device discussed in the paper matches existing prosthetics, but also showcases the advantages of soft materials in the fabrication of those designs, as using silicon and portable fluidics helped reduce the cost, complexity and weight, making great leaps in resolving the SWaP-C problem.

Bioinspiration

Building off the previous section, as soft robotics becomes more accessible to applications outside robotics specifically, another interesting aspect that is brought up in the field is bioinspiration. Han and Harnett provide a short overview on how the design of anthropomorphic hands inspired from biomechanics of human hands has resulted in more biomimetic soft grippers. However, observing the wider literature reveals interesting work that move away from anthropomorphic form factors towards more exotic versions such as designs mimicking the grasping patterns of octopus tentacles. Commercially available versions of tentacle-based grippers have also been revealed, notably the 2017 Festo TentacleGripper. Adapting this morphology to typical prosthetic design may result in interesting grasping behaviours that might prove to supplement motor functions currently not possible with current prosthesis designs.

Broader Impacts and Future Work

In the US, many middle-aged to elderly people undergo surgery to amputate limbs due to complications brought about by vascular and other related diseases (varicose veins, diabetes, etc.). Many cases dealing with loss of limb also arise from workplace accidents (soldiers on the battlefield, workers on oil rig, mines, and other hazardous environments, etc.). Living without a limb has its own challenges, as actions once taken for granted are now exceedingly difficult—a lower limb amputee will not be able to walk unassisted while an upper limb amputee will not be able to perform tasks that require dexterous manipulation. Even those that use prostheses suffer from biomechanical disadvantages due to the nature of the device not being fully able to mimic true human motion. Over time, having to overcompensate in terms of motion makes amputees more likely to develop complications such as joint pain and osteoporosis/osteopenia16.

At the end of this review, having seen the various specific trends that have arisen in the field, we may extrapolate the broader impacts of these technologies and speculate on specific convergent applications leveraging advances in both fields:

- Regaining Touch: Similar to the aforementioned soft neuroprosthetic, different soft sensors can be adapted to anthropomorphized contexts to provide different types of tactile feedback. My own research in this area adapts magnetic sensors for 3D force feedback; this can be combined with tangential works such as robotic skins, working towards giving prosthetic wearers the same depth of perception that our own human skin provides.

- Beyond Human Biomechanics: As we move closer towards mimicking human range of motion, one idea I find interesting is the possibility of incorporating different grasping ‘forms’ than the simple human finger. Seeing the adaptability of the octopus tentacle and grippers based off that design, I think having a bionic device with tentacles instead of fingers—while looking straight out of science fiction—opens the door to many new designs that move beyond what the human form can do.

- Reducing the Barrier to Entry: Since soft materials like silicone and technologies like 3D printing have become cheaper and easier to use, combining the proliferation of existing 3D printed prosthetics with advances in multi-material printing may result in advanced sensing and design capabilities becoming even more accessible to the layman. This appeals more towards the broader impacts observed by the NSF as it can be researched as a method to bring technologies like this to the masses.

Thus, utilizing the advances discussed in this review, we may see advances in soft robotics that can contribute greatly towards reducing SWaP-C for the different aspects discussed earlier, and that combined with advances is making lifelife prosthetics and better neural control schemes will overall increase the quality of life of prosthesis wearers.

References

- Y. Guo, L. Liu, Y. Liu, and J. Leng, “Review of Dielectric Elastomer Actuators and Their Applications in Soft Robots,” Advanced Intelligent Systems, vol. 3, no. 10, p. 2000282, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aisy.202000282 ↩︎

- A. Marinelli, N. Boccardo, F. Tessari, D. D. Domenico, G. Caserta, M. Canepa, G. Gini, G. Barresi, M. Laffranchi, L. D. Michieli, and M. Semprini, “Active upper limb prostheses: a review on current state and upcoming breakthroughs,” Progress in Biomedical Engineering, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 012001, Jan. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2516-1091/acac57 ↩︎

- P. W. Moxey, P. Gogalniceanu, R. J. Hinchliffe, I. M. Loftus, K. J. Jones, M. M. Thompson, and P. J. Holt, “Lower extremity amputations — a review of global variability in incidence,” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 28, no. 10, pp. 1144–1153, [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezpv7-web-p-u01.wpi.edu/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03279.x ↩︎

- M. Windrich, M. Grimmer, O. Christ, S. Rinderknecht, and P. Beckerle, “Active lower limb prosthetics: a systematic review of design issues and solutions,” BioMedical Engineering OnLine, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 140, Dec. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12938-016-0284-9 ↩︎

- M. Zhu, S. Biswas, S. I. Dinulescu, N. Kastor, E. W. Hawkes, and Y. Visell, “Soft, Wearable Robotics and Haptics: Technologies, Trends, and Emerging Applications,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 110, no. 2, pp. 246–272, Feb. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9686045 ↩︎

- K. Wendo, O. Barbier, X. Bollen, T. Schubert, T. Lejeune, B. Raucent, and R. Olszewski, “Open-Source 3D Printing in the Prosthetic Field—The Case of Upper Limb Prostheses: A Review,” Machines, vol. 10, no. 6, p. 413, Jun. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1702/10/6/413 ↩︎

- K. Gilday, J. Hughes, and F. Iida, “Sensing, Actuating, and Interacting Through Passive Body Dynamics: A Framework for Soft Robotic Hand Design,” Soft Robotics, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 159–173, Feb. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/soro.2021.0077 ↩︎

- Amputation Levels Names,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://amputeesqld.org.au/introduction-to-amputation-surgery/amputation-levels-names ↩︎

- H. H. Huang, L. J. Hargrove, M. Ortiz-Catalan, and J. W. Sensinger, “Integrating Upper-Limb Prostheses with the Human Body: Technology Advances, Readiness, and Roles in Human–Prosthesis Interaction,” Apr. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-110222-095816 ↩︎

- J. Park, M. Chang, I. Jung, H. Lee, and K. Cho, “3D Printing in the Design and Fabrication of Anthropomorphic Hands: A Review,” Advanced Intelligent Systems, vol. n/a, no. n/a, p. 2300607. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aisy.202300607 ↩︎

- P. Capsi-Morales, C. Piazza, M. G. Catalano, G. Grioli, L. Schiavon, E. Fiaschi, and A. Bicchi, “Comparison between rigid and soft poly- articulated prosthetic hands in non-expert myo-electric users shows advantages of soft robotics,” Scientific Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 23952, Dec. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02562-y ↩︎

- H. L. Ornaghi, F. M. Monticeli, and L. D. Agnol, “A Review on Polymers for Biomedical Applications on Hard and Soft Tissues and Prosthetic Limbs,” Polymers, vol. 15, no. 19, p. 4034, Jan. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/15/19/4034 ↩︎

- M. S. Han and C. K. Harnett, “Journey from human hands to robot hands: biological inspiration of anthropomorphic robotic manipulators,” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 021001, Feb. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/ad262c ↩︎

- C. Hegde, J. Su, J. M. R. Tan, K. He, X. Chen, and S. Magdassi, “Sensing in Soft Robotics,” ACS Nano, vol. 17, no. 16, pp. 15 277–15 307, Aug. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c04089 ↩︎

- Y. Shan, Y. Zhao, H. Wang, L. Dong, C. Pei, Z. Jin, Y. Sun, and T. Liu, “Variable stiffness soft robotic gripper: design, development, and prospects,” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 011001, Nov. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/ad0b8c ↩︎

- C. P. F. Pasquina, A. J. Carvalho, and T. P. Sheehan, “Ethics in Rehabilitation: Access to Prosthetics and Quality Care Following Amputation,” AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 535–546, Jun. 2015. [Online]. Available: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/ethics-rehabilitation-access-prosthetics-and-quality-care-following-amputation/2015-06 ↩︎

- G. Gu, N. Zhang, H. Xu, S. Lin, Y. Yu, G. Chai, L. Ge, H. Yang, Q. Shao, X. Sheng, X. Zhu, and X. Zhao, “A soft neuroprosthetic hand providing simultaneous myoelectric control and tactile feedback,” Nature Biomedical Engineering, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 589–598, Apr. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www-nature-com.ezpv7-web-p-u01.wpi.edu/articles/s41551-021-00767-0 ↩︎

Leave a comment