Robot control interfaces are of paramount importance for human-robot collaboration, as they facilitate the expression of human intent to the robot. The interaction is influenced by the characteristics of each input device and method. This project examines various input interfaces that accelerate human-robot communication for specific applications and evaluates the results of a user study completed with these interfaces. The aim is to better comprehend the systemic consequences of these interfaces and to provide a trustworthy foundation for designing more user-friendly systems.

Thanks to Edwin Clement and Thanikai Adhithiyan Shanmugam for working with me on this project!

As the field of robotics progresses, and robots become increasingly integrated into collaborative applications, communication methods with these machines have likewise advanced1. From traditional, slow, and offline computer-based waypoint selection for industrial robots2 to contemporary approaches utilizing real-time technologies such as ChatGPT3, there is now a plethora of ways for humans to convey their intent to robots. Given the wide array of input devices available, the user experience of employing each device varies across individuals and tasks. Some individuals may prefer the immersive nature of Virtual Reality (VR)4, while others may be more comfortable visualizing the robot’s movements using tools like RViz5 and communicating their intent accordingly.

Prior research has explored how different interface types, such as computer-based interfaces, VR, or human-factor-related interfaces (e.g., voice or gestures), impact the level of immersion in Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) experiences, either positively or negatively6. Simultaneously, advancements in User Experience (UX) research have focused on designing interfaces that support and optimize the human experience, establishing quantitative metrics for assessing UX7. These developments have resulted in a convergence of the two fields in the design and development of HRI interfaces.

Proposed Methodology and Challenges

In light of the challenges encountered during the development phase after the initial proposal, the methodology underwent several modifications. This section offers a comprehensive overview of the initially suggested methodology for the sake of completeness, while also shedding light on the challenges encountered and the subsequent adjustments made to align with the current method.

Prior Methodology

A longitudinal user study was proposed to capture user’s evolving conceptions of interfaces throughout the development process in a multi-stage process:

- Develop rudimentary prototypes for interfaces.

- Conduct user interviews to elicit initial impressions and assumptions.

- Iteratively refine the interfaces based on user feedback.

- Engage users in hands-on experiments with the new interfaces.

- Evaluate performance utilizing a combination of quantitative and qualitative metrics.

- Analyse and identify common trends in behaviour associated with specific interface elements.

Control interfaces would be tested for a standard pick-place sorting application with a robot manipulator. The user would be tested on the following interfaces:

- Computer with keyboard and mouse (KBM): Standard GUI application with buttons and view of the environment.

- Virtual reality headset (VR): VR version of the same KBM environment

- Voice-activated interface (VO): Same as KBM but modelled with a voice-activated keyword-based interface

Challenges and Revisions

While adhering to the previously proposed methodology, we encountered several challenges, primarily centred around the selected implementations being overly ambitious to execute within the constrained timeframe provided. To elaborate:

- Lack of ROS2 support: Some crucial MoveIt and Gazebo libraries essential for the previously implemented framework were either unavailable for ROS2 or existed only in C++ at the time of implementation. This posed a significant challenge as it was the most formidable obstacle to overcome. Even in ROS Noetic, a few Gazebo libraries were lacking due to the developers discontinuing support beyond ROS Melodic, the initial platform for the implementation.

- URDF Inconsistent Import: The import pipeline from the Robot Definition file to Unity proved to be cumbersome, exhibiting inconsistencies and failing to transfer all meshes/surfaces seamlessly.

- Lack of Computational Power: The initially proposed approach for the Audio Interface relied on the Google SayCan8 method. This method, utilizing a 540 million parameter model, predicted a set of intents and matched them with action commands to determine the optimal action. Due to constraints in computational power and time required for training the dataset, a shift was made to a more resource-efficient model that could deliver comparable performance to the SayCan Model.

To mitigate the risk of those challenges, the following changes were implemented:

- ROS Noetic upgrade: Given the impracticality of transitioning to ROS2 and the obsolescence of the ROS Melodic framework, the decision was made to upgrade the packages to ROS Noetic. This transition, retaining the codebase in Python, ensured flexibility and leveraged the robust support available for this platform.

- KBM application modifications: Owing to the absence of certain packages beyond ROS Melodic, significant adjustments were made to the application. Key features were omitted or transformed, including substituting Gazebo and rqt-GUI with a more comprehensive RViz-based implementation. Furthermore, the Universal Robots UR5 was replaced with a Franka Emika Panda. The environmental setup also underwent modifications to introduce more variations, allowing for diverse hardware devices, and moving away from a reliance solely on software.

- Google Recognizer & Word2Vec Model: With the constraint of computational cost in consideration, we devised an alternative architecture expected to perform comparably to the SayCan Model. This architecture comprises an Automated Speech Recognition (ASR) module, integrated from the Google Recognizer, as its initial component. For intent prediction, we implemented the Word2Vec Model, which forecasts both the colours and the intended action to be executed.

Revised Interfaces

Following from the challenges and their changes outlined in the previous section, this section outlines in detail the currently executed implementation, describing the new interfaces designed for the user study.

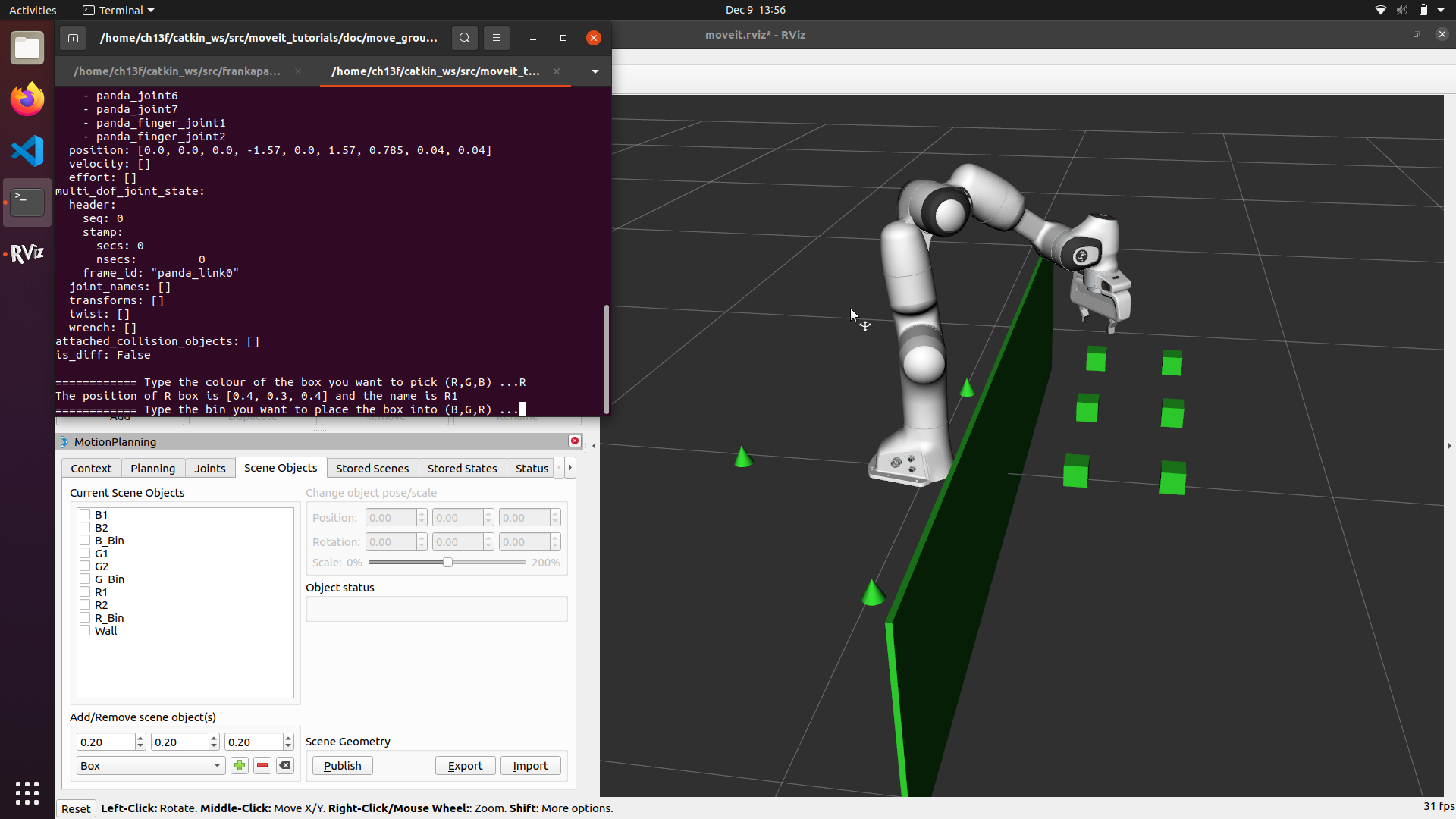

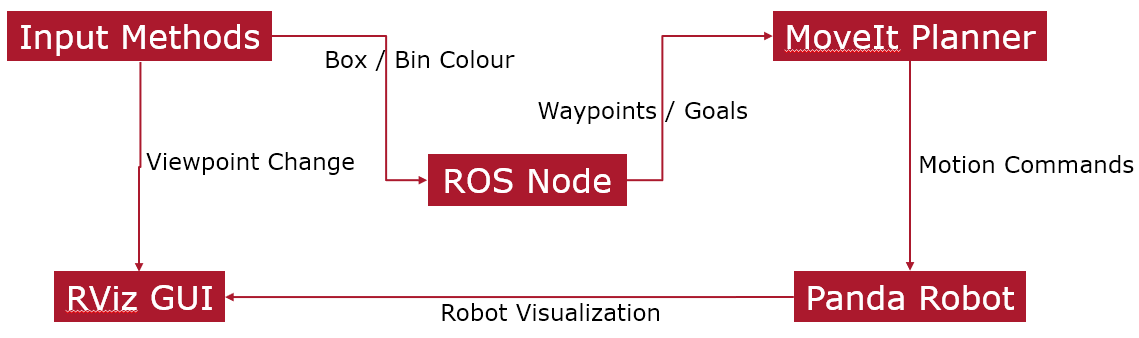

KBM Interface

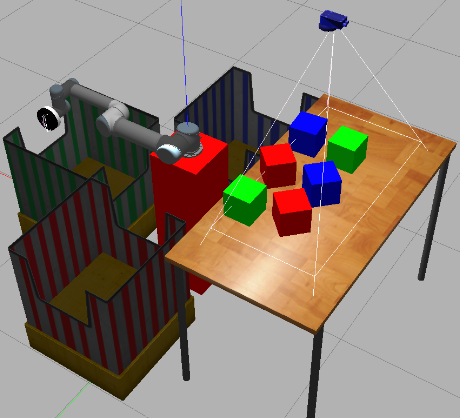

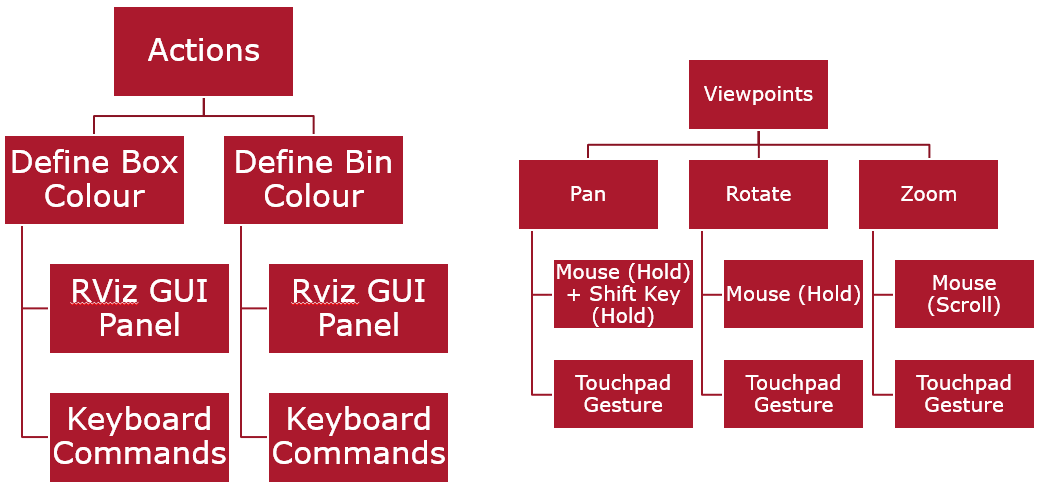

The principal interface, namely the KBM interface, underwent extensive modifications as it served as the backbone of the setup. We opted for the Franka Emika Panda manipulator due to its seamless integration with MoveIt and RViz, aligning with our project requirements. Given that we constructed the entire environment in RViz, we maintained simplicity while exploring diverse ways to utilize the interface. For instance, we examined how users performed with a terminal-based command interface compared to the GUI panels provided by RViz, offering granular control over the application. Furthermore, we investigated how user preferences might shift when presented with a touchpad as an alternative to the “control ball.” This control ball is a tool employed to maneuver the robotic arm and set goal poses for motion planning for the robot.

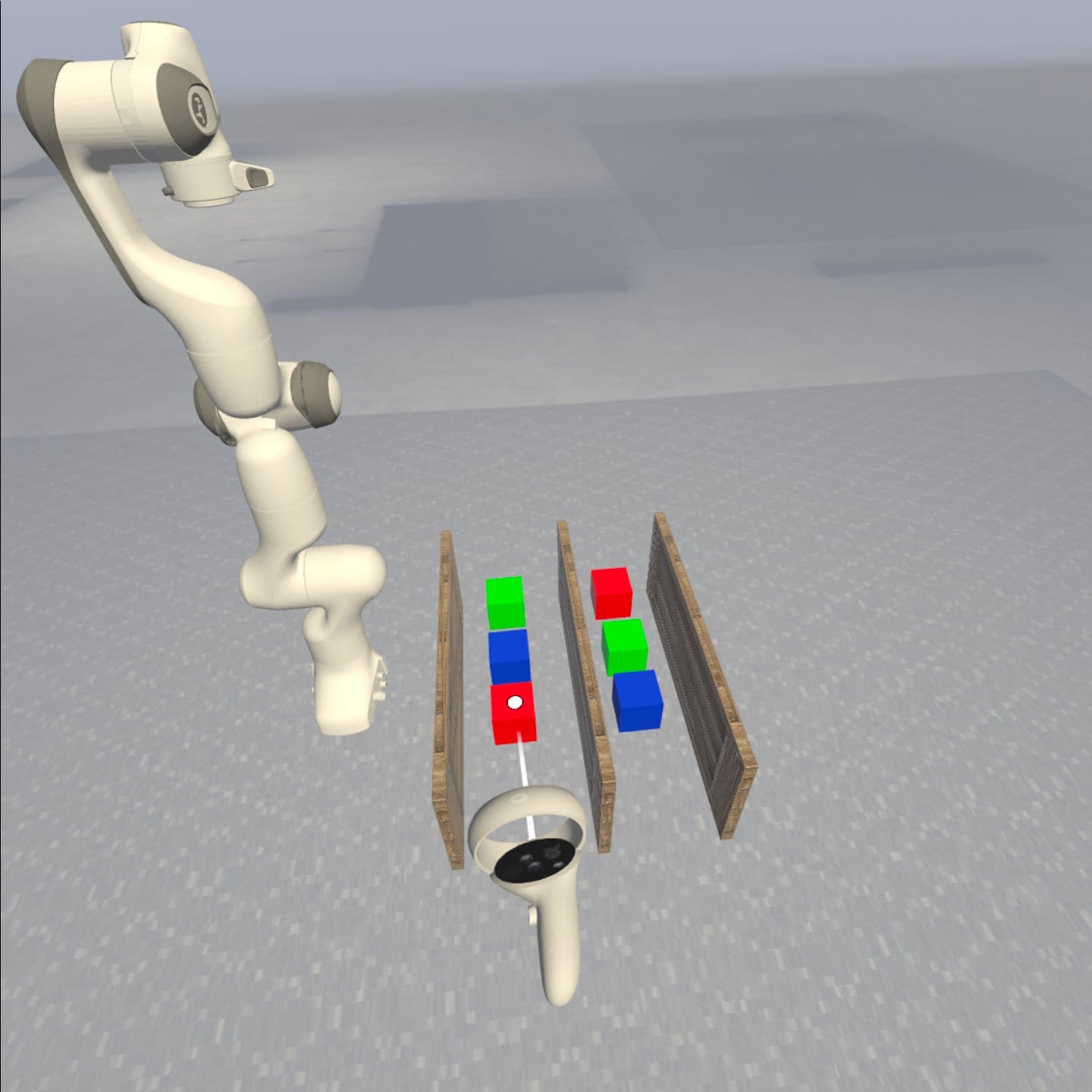

VR Interface

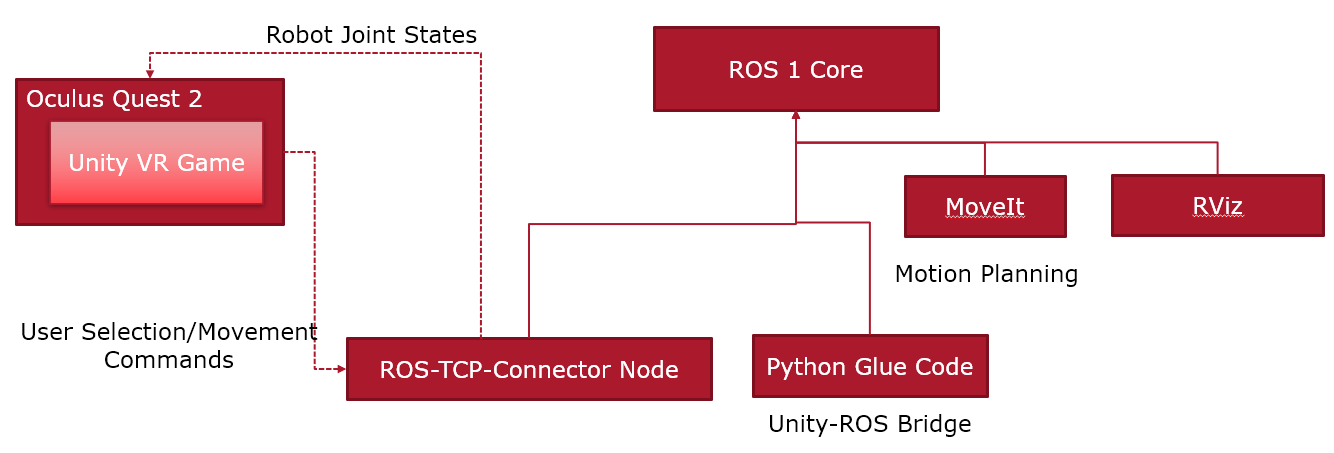

The VR interface is developed on Unity Platform on the Meta Quest XR Plugin ecosystem. We utilized the URDF importer for loading in the Robot and added in controller code over C#. This communicated over to the ROS Noetic system over TCP Sockets using ROS-TCP-Connector. The users were informed of the various implemented mechanisms to move around and accomplish the task.

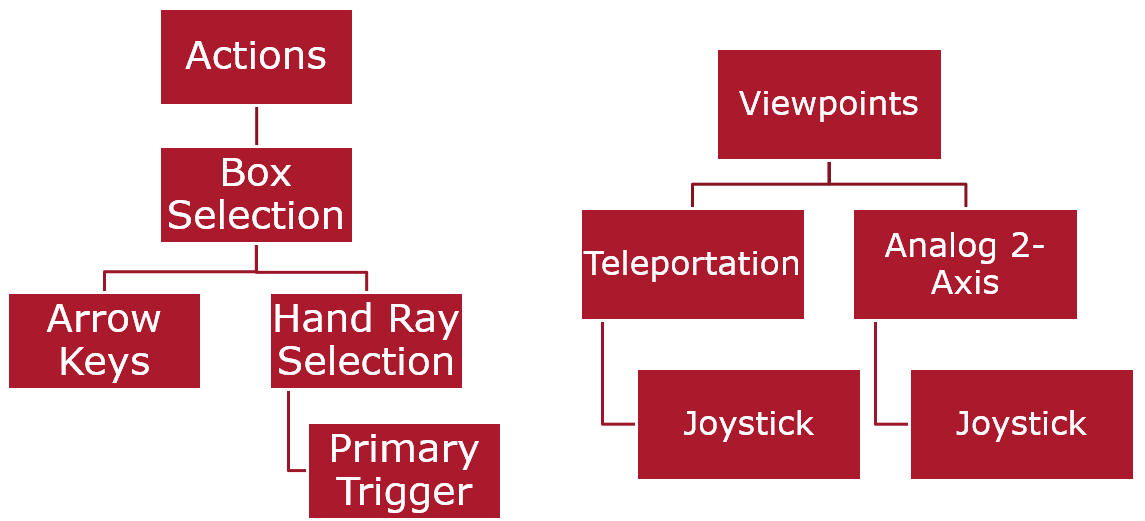

- Motion Controls: Teleportation; Joystick Motion

- Objective Selection: Select via Joystick on a carousel; Ray Casting

Initially, the Unity Engine and ROS 2 were connected over ros2-for-unity. However, due to issues on the motion planning and other library support, we downgraded to ROS 1, thereby having to use ROS-TCP-Connector which caused some trouble in integration.

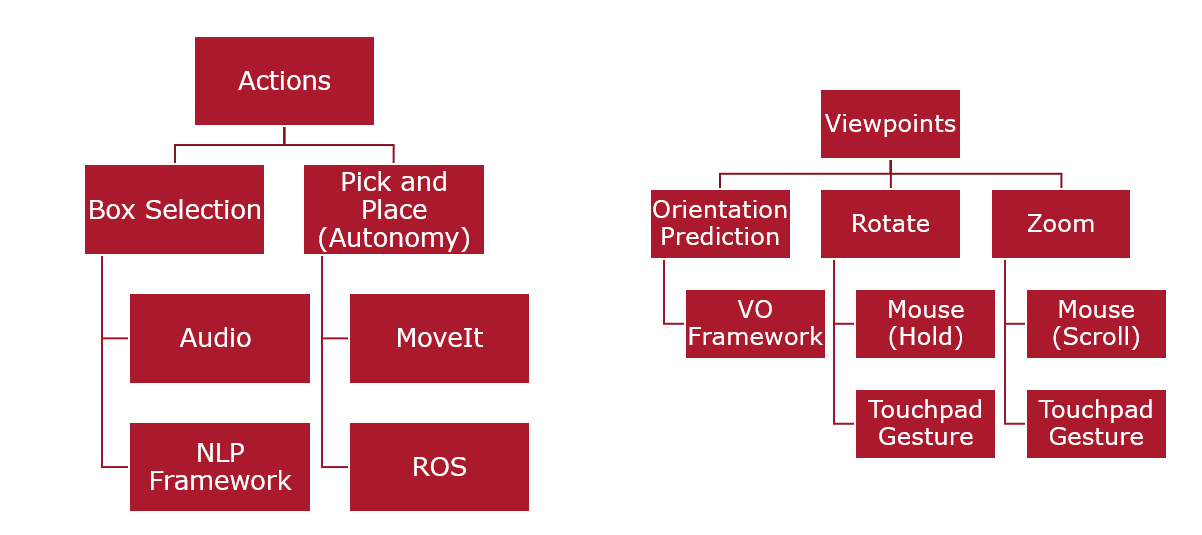

Voice-activated Interface

The restructuring of the voice-activated interface architecture was necessitated by computational constraints and excessive time consumption. The revised architecture maintains the foundational structure, consisting of an Automated Speech Recognition (ASR) module followed by an Intent Prediction model. The user records or speaks through the system microphone, and the audio is converted into a string of characters using the ASR module. The chosen architecture for speech recognition is the Google Recognizer. Subsequently, the string is forwarded to the Word2Vec model, serving as the Natural Language Understanding (NLU) module. This model converts the strings into keywords representing the actions and colors. The system is then integrated with the Keyboard and Mouse (KBM) interface and the Panda manipulator, facilitating the execution of the intended actions.

Architectures and Userflows for the three proposed interfaces.

User Study

Upon completion of the interface design, we enlisted the participation of friends and colleagues in a user study. The user study aims to test two hypotheses:

- There is a discernible mapping between specific human intents and control interface elements.

- It is feasible to leverage this mapping to deduce intent from the utilization of interface elements, and conversely, to utilize interface elements to enforce a particular method of expressing intent.

The study encompassed 10 participants representing diverse demographics, with varying levels of expertise and familiarity with the tools and interfaces intended for use. All subjects were familiar and comfortable with VR technology, displaying no indications of VR sickness or associated disorders. Subjects received a comprehensive briefing on the application, the diverse interfaces slated for testing, and their roles in the study. They were introduced to an array of input devices utilized in the experiment and probed with questions regarding the ease of use, anticipated behaviors of specific interface elements, and, upon inspection, were re-evaluated to ascertain if the mapping of elements to operations made sense to them.Subsequently, subjects were presented with the environment and instructed to execute the task while articulating their thought process. Quantitative metrics, including movement, actions, and time taken, were automatically measured using various software tools embedded within the applications or through third-party applications. In instances where such automated support was unavailable or challenging to implement, we resorted to recording the subjects for manual measurement of these metrics.

During the course of the study, we analyzed the following metrics:

- Quantitative: Time taken; Actions performed; Viewpoints changed

- Qualitative: Usability; Situational Awareness; Comparison of existing alternative devices

Quantitative metrics were measured through separate scripts running on the computer or through the observers manually recording the execution and identifying the same, while qualitative metrics were measured through the NASA-TLX and SAGAT frameworks. During the execution of the user study, several interesting trends emerged, which we would like to highlight in this section:

Irritation using Touchpad

Users consistently expressed irritation when using the touchpad in the absence of explicit left/right mouse click buttons. The touchpad introduced relative ambiguity to input, and as one subject articulated, “Having separate buttons is better.” There was unanimous agreement across all subjects that the traditional mouse was preferred over the touchpad, with some subjects expressing a preference for the “normal” mouse orientation over the vertical one.

Preference of Viewpoints:

The majority of users displayed a preference for isometric viewpoints when performing tasks. They cited familiarity as the primary reason, with statements such as “It just feels right” being echoed by several subjects. Notably, there was resistance toward alternative viewpoints being set as the default, to the extent that when users were presented with a different viewpoint before commencing the task, they attempted to shift back to the isometric view before exploring other perspectives.

Dislike of Teleportation Travel:

Through the experiments we figured out that users did not prefer to teleport around the room even though that modality gave a way to quickly grasp the scene. Interestingly, users who were moderately experienced with VR were able to quickly utilize the teleportation trick and navigation the environment much quicker than one that would use KBM interface as that ties into human spatial understanding.

Intuitiveness of Ray-Cast Selection:

For the object selection mechanism, users overwhelmingly used the ray-casting method. This is understandable, given that its intuitive and accessible. On the other hand, poke interaction while intuitive, needed a lot more movement and was treated second to Ray-Casting which could be done from a distance.

Analysis and Discussion

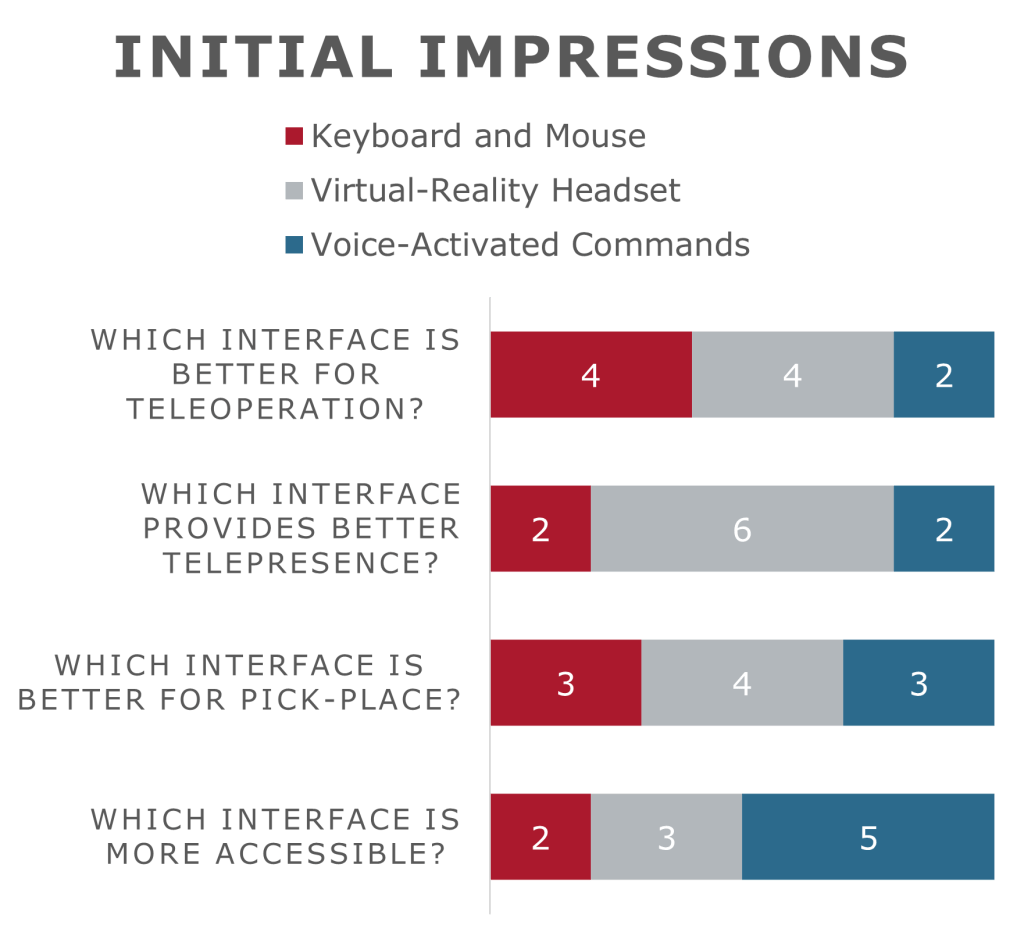

Observing the graphs, the depicted split in opinions among the subjects is evident. The subjects exhibited a notable division in their preferences for teleoperation interfaces, especially in the context of pick-place tasks. There was a discernible inclination towards VR for telepresence in general, and Voice-Operated VO interfaces for improved accessibility. However, upon further inquiry, responses were often associated with the desired level of control: participants familiar with desktop tools leaned towards KBM interfaces, appreciating the grounded experience it offered for pure teleoperation. Conversely, those favoring VR expressed a preference for a more hands-on interaction with the environment. This observation could potentially serve as a pertinent meta-inference worth consideration.

During the experiment, the time taken to complete the experiment, number of actions/commands performed, and number of times the viewpoint was changed was tracked. As can be observed, due to the time taken to record commands, the VO interface took the most time on average to complete the tasks, while VR due to its multimodal nature took the least amount of time. On the other hand, looking at the very low number of actions and viewpoint changes, it can be postulated that due to the deliberateness of commands required to interact with the framework, the interface promoted a slower pace of interaction compared to the “frantic” VR interactions logged.

Participant Experience

In response to the first question assessing the mental workload of the interfaces, the KBM interface emerged as the most demanding. This heightened demand was attributed to the necessity of simultaneously managing multiple panels within the user’s field of view, resulting in a substantial cognitive workload. Unexpectedly, the VO interface was rated as more demanding than the VR interface. Participants cited the restrictive nature of keyword-based interaction as a significant contributing factor, and it was suggested that implementing natural language could potentially alleviate this challenge.

Regarding the second question, which focused on the pace of the task and the engagement it demanded, no significant differences were found among the interfaces, as no specific time limit was imposed. However, participants using the KBM interface reported a sense of feeling rushed, likely stemming from the previously mentioned high cognitive workload associated with that interface.

For the third question, participants were asked to rate their sense of task completion rather than the actual task progress. The KBM interface received the lowest score, aligning with previous findings, while VR scored the highest. VR’s superior rating was attributed to users feeling more engaged, possibly due to the multimodal nature of VR providing spatial, visual, and additional stimuli simultaneously, contributing to a heightened sense of telepresence.

The fourth question, which assessed user stress, yielded a clear preference for VR and VO as low-stress interfaces. Apart from the earlier observations, this preference may also be attributed to the lower number of elements users needed to interact with during the task, leading to reduced overall stress.

The final question, though not central to the analysis, was included to offer a holistic view of user sentiment towards the interfaces. Users expressed dissatisfaction with the usability of the KBM interface, which may have influenced their overall low ratings for this interface. However, the notable differences in ratings for the other questions suggest that this effect may not have significantly skewed the overall findings.

Since questionnaires are subjective in nature, we used a technique called inter-rater agreeability, which is represented by Cohen’s kappa coefficient, defined by:

Here,

Conclusion

Through the user study, we unequivocally confirmed the first hypothesis, affirming that a clear one-to-one mapping exists between the design of interface elements and the perceived intent expressed by users. The robustness of this mapping was notably influenced by the explicitness of the elements themselves. For instance, elements like “move camera” exhibited a more explicit mapping compared to the more ambiguous “move,” where the interpretation could vary between moving the camera or the object in the environment.

The second hypothesis was conditionally validated, indicating a cause-effect relationship between elements and intent. In essence, we observed a correlation and demonstrated the ability to enforce specific methods of expressing intent. However, resistance from users, particularly those with prior experience in expressing intent through certain methods, was evident. This led to the recognition of an inverse scenario where elements could to be designed to accommodate user “stubbornness” towards a particular method.

Throughout the project, despite encountering challenges, valuable learning experiences were gained in various software stacks. The endeavour also provided insights into conducting user studies and optimizing products for user-study friendliness. Recognizing the benefits of explicit architectural planning, we acknowledged the importance of ensuring package compliance and averting potential complications. Furthermore, the project enhanced proficiency in asynchronous work, particularly in setting up deliverables and communication channels that account for time zone differences.

In conclusion, the project successfully achieved its objectives, offering insights into the realm of Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). Future endeavors may involve exploring the mapping concept more comprehensively or developing interfaces and applications that capitalize on this understanding.

References

- E. Rosen, D. Whitney, E. Phillips, G. Chien, J. Tompkin, G. Konidaris, and S. Tellex, “Communicating and controlling robot arm motion intent through mixed reality head-mounted displays,” The International Journal of Robotics Research, vol. 38, no. 12-13, pp. 1513–1526, 2019. ↩︎

- E. Hagg and K. Fischer, “Off-Line Programming Environment for Robotic Applications,” IFAC Proceedings Volumes, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 155–158, 1990. ↩︎

- A. Pandya, “Chatgpt-enabled davinci surgical robot prototype: Advancements and limitations,” Robotics, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 97, 2023. ↩︎

- C. Maragkos, G.-C. Vosniakos, and E. Matsas, “Virtual Reality Assisted Robot Programming for Human Collaboration,” Procedia Manufacturing, vol. 38, pp. 1697–1704, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351978920301104 ↩︎

- H. R. Kam, S.-H. Lee, T. Park, and C.-H. Kim, “RViz: a Toolkit for Real Domain Data Visualization,” Telecommunication Systems, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 337–345, Oct. 2015. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11235-015-0034-5 ↩︎

- E. Triantafyllidis, C. Mcgreavy, J. Gu, and Z. Li, “Study of Multimodal Interfaces and the Improvements on Teleoperation,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 78 213–78 227, 2020. ↩︎

- F. Lachner, P. Naegelein, R. Kowalski, M. Spann, and A. Butz, “Quantified UX: Towards a Common Organizational Understanding of User Experience,” in Proceedings of the 9th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, ser. NordiCHI ’16. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016. ↩︎

- M. Ahn et al., “Do As I Can, Not As I Say: Grounding Language in Robotic Affordances,” 2022. ↩︎

Leave a comment