This article discusses the application of systems engineering principles to the design and development of prosthetics, emphasizing collaboration among stakeholders in medicine, manufacturing, and amputee communities. With an increasing number of amputations due to medical conditions and accidents, the need for affordable and effective prosthetic solutions is critical. The proposed system seeks to streamline the production process through 3D printing to expedite fabrication while addressing high costs and rehabilitation timelines. Stakeholders’ specific roles and requirements are highlighted to ensure compliance and functionality, ultimately aiming to improve the lives of amputees and support their reintegration into society.

In the US, a large portion of middle-aged to elderly people undergo surgery to amputation limbs due to complications brought about by vascular and other related diseases (varicose veins, diabetes, etc.). A lot of cases dealing with loss of limb also arise from workplace accidents (soldiers on the battlefield, workers on oil rig, mines, and other hazardous environments, etc.). An estimated 2 million persons are living with limb loss in the United States, and this number is expected to increase rapidly as an estimated 185,000 persons undergo an amputation each year1.

The prohibitive cost of surgery due to the healthcare system aside, amputees also may deal with post-surgical complications, such as phantom pain or nerve twists2, not to mention the loss of wages due to them being deemed unfit for work. At least 36% of amputees are also past retirement age, so they do not have any sources of income to bring themselves back to a stable financial level. All these lead to up to at least $509,275 in projected lifetime costs on the part of the patient3. Living without a limb can also have its own challenges, as actions once taken for granted are now exceedingly difficult – a lower limb amputee will not be able to walk unassisted; an upper limb amputee will not be able to perform tasks that require dexterous manipulation4 – which is where prosthetics and mobility aids serve to aid patients so they may try to resume normalcy in some shape or form56. However, prosthetics themselves are very expensive, and this additional cost on top of the costs incurred so far prevents many from seeking prosthetic aids7.

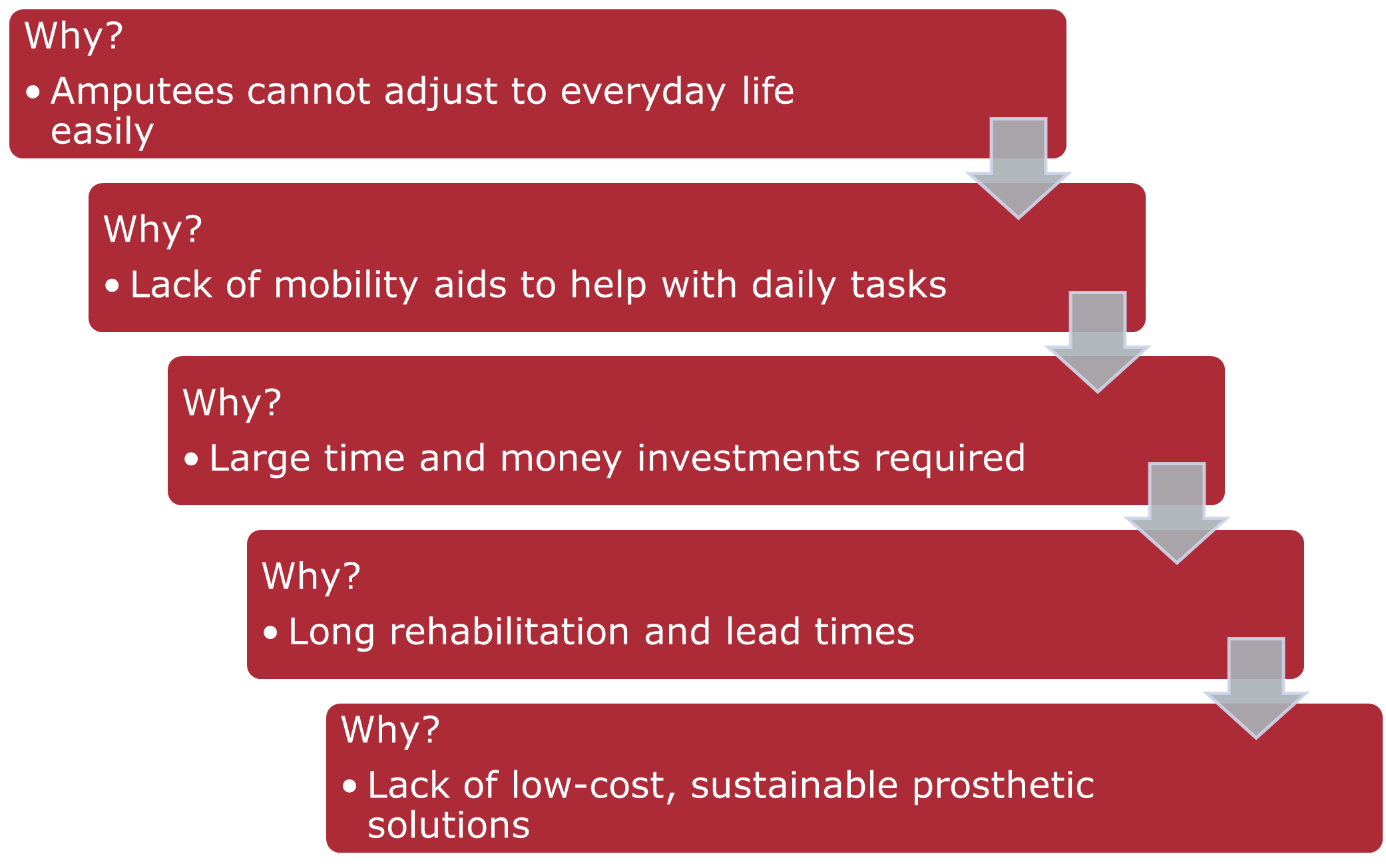

Formulating the Needs Statement

To find out the root cause behind the problem, we will use the 5-Why approach to extract further information about the problem space as we dig deeper. We can trace the initial issue of the high post-surgery impact on amputees’ lives from their inability to adjust to daily life right down to the processes they are subject to post-surgery, especially the lack of effective prosthetic solutions that are cheap and effective.

Based on the info above, we can proceed to formulate the needs statement:

Prosthetic limbs for amputees are very expensive, requiring long periods of rehabilitation therapy and waiting for custom-made prosthetics, which prevent many amputees and those born without limbs from obtaining better mobility, leading to compounded financial and value-based losses down the line. A low-cost, sustainable process for prosthetic solutions is needed to shorten the acquisition time of prosthetics and quicken therapy timelines to enable amputees to integrate with society much faster.

Identifying Stakeholders and Requirements

The three major pillars in the whole process are described below. This section focusses on the main deal-breakers that each stakeholder would have, but additional requirements that appear relevant to us will be explored as we progress.

Medical Professionals

These include doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, and other professionals involved in the primary care process immediately after surgery and during the rehabilitation process of the patient.

- Role

- Quality Assurance – ensure adherence to medical standards and processes throughout the lifecycle.

- Interactions with Other Stakeholders

- Amputees: Document recovery progress

- Manufacturers: Verify fabrication processes

- Requirements

- Quality checks put in place to ensure adherence to standards

- Integration of process into existing medical frameworks

Manufacturers

These include additive manufacturing companies and makers of 3D-printing machines, which are central to the creation of the prosthetic models used by the patients.

- Role

- Manufacturing – Creation of the machines and assistance with the fabrication of the system.

- Interactions with Other Stakeholders

- Amputees: Deliver the product for use

- Medical Professionals: Receive data from field-testing

- Requirements

- Cost-effective modification of existing infrastructure

- Sustainable models for long-term manufacturing

Amputees

They are the end-user of the finished product.

- Role

- Customer – The user of the completed prosthetic system.

- Interactions with Other Stakeholders

- Medical Professionals: Consult on type of prosthetics to be made

- Manufacturers: Submit prosthetics for maintenance when needed

- Requirements

- Reduction of product lead time and purchase costs

- Ease of use and comfort

Operational Concept

We will now recreate a few hypothetical scenarios to formulate a holistic picture of the system operation and understand stakeholder interactions in more depth to formulate architectural requirements later:

Scenario 1 — Upper Limb Prosthetic

A worker in a chemical factory suffers an accident on the shop floor involving a boiler explosion, rendering him unable to use his left arm from the elbow down. He undergoes surgery to amputate the affected area from the body. He does not suffer any post-surgery complications. On consulting with his primary care provider, he decides to opt in to receive a prosthetic arm for general use.

The medical professional discusses further actions with the amputee and records the dimensions of their right arm, aiming to mirror the same on the prosthetic. The dimensions will be provided to the manufacturer, which include forearm girth and length, hand-palm size, and finger dimensions as the main quantities.

The manufacturer receives the dimensions from the medical professional along with instructions on the various restrictions to be kept in mind during design. With the parameters provided, a suitable material is selected, and the prosthetic arm is designed and manufactured with a simple design keeping in mind the general-use requirement. Due to the fast nature of 3D printing technology, the arm is completed in a very short time and can be tested in rehab itself.

In the meantime, the amputee undergoes rehabilitation to prepare for the installation of the new prosthetic arm. Since the completed arm is prepared in a short period of time, it can be used for the next set of rehab sessions simultaneously. During the session, the medical professional keeps track of any potential distress factors noted by the amputee and sends feedback to the manufacturer to incorporate these changes.

Once the modifications have been done, the user is able to finish their rehabilitation with a brand-new prosthetic arm at a fraction of the cost and time of a conventional arm. The medical professional certifies the amputee as fit to work, as his original job did not involve lifting heavy weights. As the whole arm is 3D printed, it is easy to maintain and replace as the manufacturer has the case on file and can recreate it when necessary.

Scenario 2 — Lower Limb Prosthetic

A middle-aged office worker gets into a car crash, rendering both legs unable to be saved. He is amputated from the lower knee down on both legs. In consultation with the medical professional, he expresses his desire to continue his hobby of long-distance running, but due to the long wait time for sports prosthetics decides to opt-in for a temporary lower limb prosthetic solution in the meantime while the main prosthetic is built.

The medical professional takes essential measurements of the amputee’s legs and, using the history of similar cases on file, creates the requisite dimensions such as shin length and girth, ankle brace, etc. to send to the manufacturer. Since the prosthetic is to be used on a weight-bearing limb, the manufacturer chooses to implement a composite of 3D printed parts assembled around a core metal frame, which takes slightly longer than a conventional all-metal prosthetic. As a temporary measure a fully 3D printed leg is supplied for rehab.

The amputee undergoes rehabilitation with the 3D printed prosthetic while the manufacturer develops the main one. This allows the medical professional to record data much faster to send to the manufacturer so the main prosthetic may be tweaked accordingly while also giving the amputee the experience of the prosthetic without waiting. The amputee is able to finish rehab with the 3D printed prosthetic and is certified for work by the medical professional, continuing with his daily life while the metal prosthetic is built.

Once the manufacturer finally builds the composite prosthetic, the amputee undergoes a second much shorter session of rehab to adjust to the new prosthetic and is able to adjust to the new prosthetic very quickly due to prior exposure to the temporary prosthetic. While the cost has not decreased by a large amount, the reduction in lead time and comfort are vastly increased. The manufacturer requires the amputee to submit the prosthetic for maintenance annually, wherein the temporary prosthetic is provided for the amputee to continue his daily life while it is being maintained.

Architecture Diagramming

Armed with the contextual information from the operational concept and the stakeholder requirements, we can now begin to visualize further system concepts.

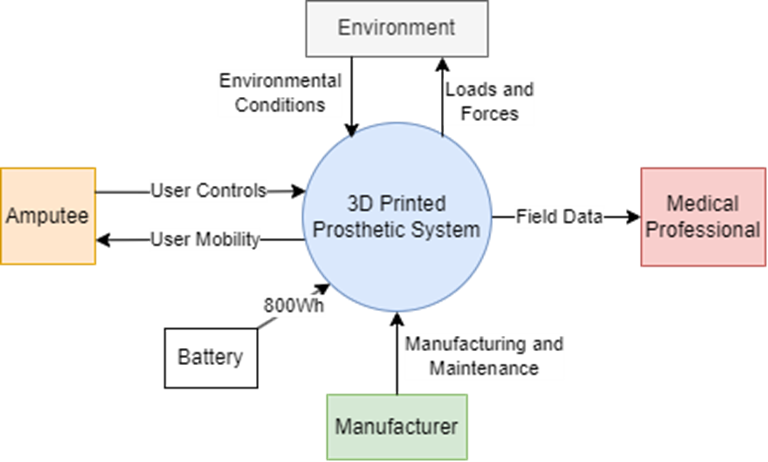

System Context Diagram

The following diagram effectively summarizes the interactions of the various stakeholders with the system when in operation.

Aside from the interactions between stakeholders during development, when the system in in operation, the main interactions of the system with the stakeholders are depicted above. To elaborate on the relations:

- Medical Professionals

- Receive: Field data from the prosthetic detailing the amputee’s activities and usage patterns

- Manufacturers

- Supply: Manufacturing and Maintenance activities for the upkeep of the system

- Amputee

- Supply: User Controls and inputs to the control system

- Receive: User Mobility response from the system to enable motion

- Environment

- Supply: Physical Conditions and on the system to be borne by the mechanism

- Receive: Loads and Forces exerted by the system on objects in the environment

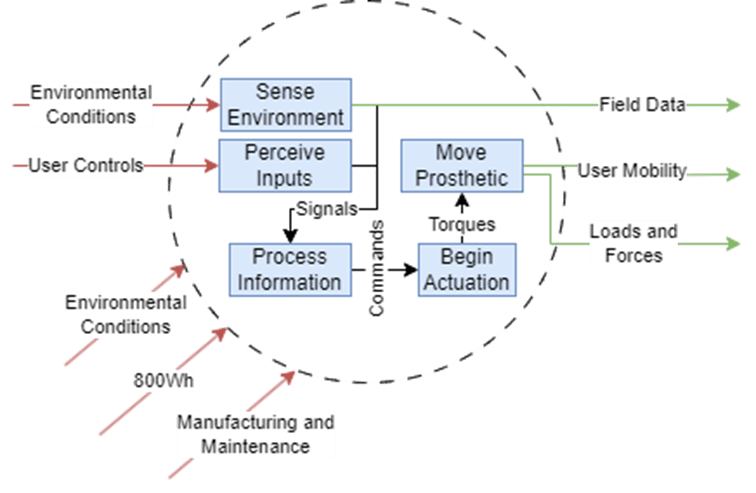

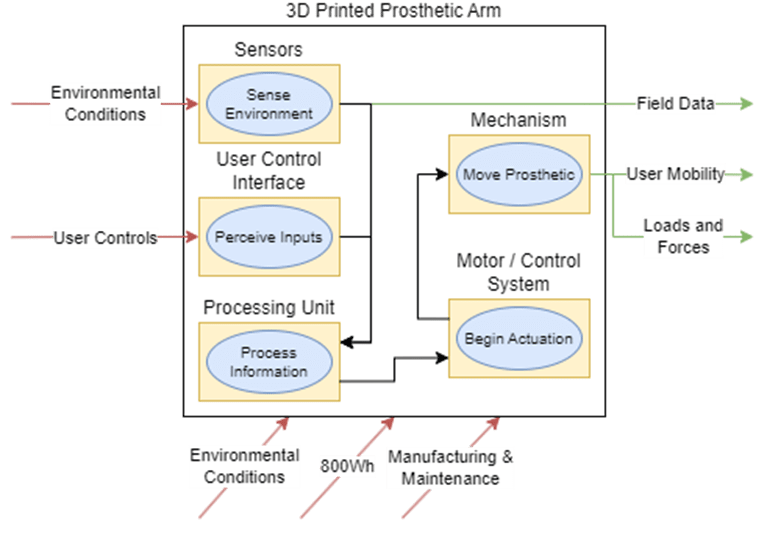

Functional Block Diagram and Notional Architecture

These diagrams build on the context diagram shown previously and demarcate various subsystems that would handle certain system inputs and outputs.

To elaborate on each subsystem shown and their role in the architecture:

Sensors

- Inputs

- Environmental parameters such as temperature, force, etc.

- 800Wh power from the Battery

- Outputs

- Signals to influence the Information Processor

- Field Data to dispatch to the Medical Professional

User Control Interface

- Inputs

- User Controls as to the intended action to perform

- 800Wh power from the Battery

- Outputs

- Signals to indicate user actions to the Information Processor

Information Processor

- Inputs

- Signals from Sensors and User Control Interface to perform calculations

- 800Wh power from the Battery

- Outputs

- Commands to motors to execute motions

Motors

- Inputs

- Commands from the Information Processor to execute motions

- 800Wh power from the Battery

- Outputs

- Actuation Torques that move the Mechanism of the system

Mechanism

- Inputs

- Torques from the motors to move the Mechanism

- Environmental Conditions such as weather, weights of objects being handled, etc. that affect the Mechanism

- Outputs

- Loads and Forces on objects in the Environment

Candidate Architectures

Now that we have a general idea of what functional and physical subsystem blocks the system would compose of, we will create various candidates that try to address the system in different ways.

Candidate 1: Cosmetic / Minimal System

These prosthetics are mostly cosmetic without the expectation that they will be used to interact with objects in a very dexterous manner. In this case, the architecture can be tailored in the following ways:

| Subsystem | Impact | Effect |

| Sensors | Low | No fine sensing |

| User Control Interface | Low | Baseline interface |

| Processing Unit | Low | No major computation |

| Motor / Control System | Low | Baseline controls |

| Mechanism | Low | High Aesthetics, Low Costs |

Candidate 2: Agile / Dexterous System

These prosthetics focus more on dexterity and allowing the amputee to manipulate objects more skilfully. Most upper-limb prosthetics will lie in this category. The tailored architecture is as follows:

| Subsystem | Impact | Effect |

| Sensors | High | Very fine sensing |

| User Control Interface | High | Sensitive and responsive interface |

| Processing Unit | High | Fast and accurate computation |

| Motor / Control System | High | Agile controls |

| Mechanism | Medium | High Aesthetics, Medium Costs |

Candidate 3: Resilient / High-Load Systems

These prosthetics are expected to sustain harsh conditions and thus would be designed to not falter under very high loads. Most lower-limb prosthetics fall into this category. The tailored architecture is as follows:

| Subsystem | Impact | Effect |

| Sensors | Medium | Some basic sensing |

| User Control Interface | Medium | Responsive and reliable interface |

| Processing Unit | Medium | Some computation |

| Motor / Control System | Medium | Reliable controls |

| Mechanism | High | High Reliability, High Costs |

Operational, Functional and Performance Requirements

Based on the above information we can now start listing the operational and functional requirements of the system.

Operational Requirements

- Medical Compliance

- Must be approved by the FDA

- Production Operations

- Must be operational for at least 2 yearsMust have a median lead time of 7 days

- Must be made from sustainable materials and processes

- User Experience

- Must not cost more than 50% of the total medical expensesMust be able to wear device for long periods of time

- Must be able to attach and remove quickly

Functional Requirements

- Medical Compliance

- Must satisfy ISO/TS 8551, 21065

- Must not have a weight more than the expected weight of the limb it is replacing

- Production Operations

- Must satisfy ISO 24562, 15032, 4549Must have an MTBF > 80,000 hours

- Must be made from biodegradable materials and satisfy IWA 42

- User Experience

- Must have total cost < 30% of totalMust have usage time > 8 hours

- Must have installation and removal time < 5 min

Performance Requirements

- Medical Compliance

- Weight must lie between 2-4 pounds for upper limb and 4-6 pounds for lower limb

- Production Operations

- Material wastage < 10%Factor of safety in design > 1.25

- Production lead time < 7 days

- User Experience

- Input response time < 0.1s

Relation to MOEs and MOPs

The requirements listed above can be listed closely to the following MOEs and MOPs:

- MOE: Comfortable Time of Usage > 8 hours

MOP: Weight, Battery Life - MOE: Dexterity of Objects within 1x1x1 in. Volume

MOP: Degrees of Freedom, Input Response Time

Verification and Validation

Since the system is heavily customized to the user and their needs, verification and validation methods are essential to ensuring that the developed system is not only medically compliant and addresses all the user’s needs but the user is able to clearly understand and implement the solution as it was designed.

Verification Events

Especially in the medical field, the stringent processes set in place ensure that the device in question is safe enough for human use. Thus, verification is the most important step in realizing a product in this space.

- Simulation and Bench Testing: During development of the prosthetic at the manufacturer’s, performing simulation tests and lab setup tests of the designed product is essential to guaranteeing its performance under certain edge conditions, keeping the functional requirements in mind.

- Medical Compliance Testing: This is a straightforward method – as long as it complies with the various ISO standards surrounding medical devices, it will be rated safe for use.

Validation Events

Validation of the product with the user guarantees satisfaction of the intended use-case and also helps prove the MOEs and MOPs discussed previously:

- User Testing: Testing the fabricated prosthetic with the amputee during physiotherapy sessions helps garner essential user feedback to validate the parameters assumed by the medical professional, and if needed provides data for the manufacturer as well to tweak the design to fit the use case better given the MOEs in mind.

- Field Data: Getting real-time data from the field use of the prosthetic in the intended environment helps the medical professional track the amputee’s progress in between physiotherapy sessions and also allows the amputee themselves to understand and relay their own experience so that a better understanding of how to operate and modify the system if needed could be reached.

System Operation and Maintenance

Operational Scope

The operational scope of the system is decided at the beginning of the SE process with the stakeholders, due to the bespoke nature of the system. This inherently helps filter out ambiguities in the CONOPs as the scenarios themselves are described within the constraints that each system candidate would be bound by, based on the stakeholder requirements at the time.

Some concerns with respect to this aspect may arise from the user themselves using the system in incorrectly specced environments – for example, a cosmetic prosthetic wearer holding on to a very heavy object with it, or a high-load prosthetic user trying to perform very delicate operations. Reliability of the electronics is also a very important factor especially in the case of dexterous prosthetic variants.

Maintenance Activities

The various maintenance activities (corrective, adaptive, perfective, scheduled) that would be put in place for the system are described contextually below:

Adjustment Period

This would be mostly towards the early stages when the user is adjusting to the prosthetic during therapy. Based on user and professional feedback garnered from the sessions any problems can be addressed and possible enhancements can be explored to fit the user’s case better

Routine Maintenance

This lies within both the operational scope and the business model that the company issuing the system may investigate. Aside from regular service of the prosthetic system – depending on use and performance this may be every 3 months to a year – the company may employ a business model that leverages providing the user with options to provide enhancements or refresh the hardware / software after the original system has completed its lifecycle. New and old users may also be asked to provide stakeholder-esque feedback for adaptive transitions from old to new technologies implemented in the system.

Project Management Process

To implement the project certain managerial processes must be setup. This section goes over each major activity as part of an SEMP (Systems Engineering Management Plan) to streamline the approach to the problem.

Decision Management

Since each prosthetic is bespoke, there is a fair amount of unique decision-making that goes into every single prosthetic. Given the effort of the proposed system to “automate” the development process in some way, it must be possible to use decision management to streamline this aspect as well. In our case, the following decisions would be required, in order of appearance in the developmental lifecycle:

- Concept

- Should the system be an upper-limb or lower-limb device?

- Should the device be cosmetic, generic, or heavy-duty?

- Development

- What are the required dimensions to prioritize during fabrication?

- Is a temporary substitute required to be provided first?

- Production

- What percentage of the device may require 3D-printing?

- How many devices are needed to be made?

- Utilization and Support

- What time period is required for maintenance cycles?

- When must the user be asked to upgrade to a newer model?

- Retirement

- Can the disposed device be repurposed elsewhere?

- What percentage of the device is sustainable?

Similar questions can also be extended to the subsystems involved in the candidate architectures described previously. The candidate architectures are tailored to satisfy certain requirements of the user, so while a single candidate cannot be selected as the de-facto option, the level of detail needed by the user for certain operations can determine what candidate architecture may be used as the base. In all cases, the patient would need to be properly sensitized to the inherent capabilities of the system to understand the limits of use — someone with a cosmetic variant cannot perform heavy-duty operations, after all.

Configuration Management

Although prosthetics are custom-made by nature, there are certain repeatable aspects of the system that can benefit from applications of an effective configuration management process. We can apply this process to the following 4 identified areas of the system:

Patient Therapy

Since there are multiple types of prosthetics that may be fitted onto a patient, the CM process would involve mapping the data collected to certain movement archetypes which will provide flexibility to the medical professional to direct their own therapy pathway better.

Device Fabrication

Depending on the movement archetype a suitable prosthetic template would be chosen to be fabricated, customized to the patient’s needs. This aspect requires CM to map the medical inferences by the medical professional to actionable design limits during fabrication, building off of those templates. This means the manufacturer can set up premade machine workflows that also account for the variations off each template to quicken manufacturing.

Field Data

When using the device, the type of data to be collected would differ during the lifetime of the system – during the initial stages more care would be taken to monitor the movement limits or response times, while during normal usage more generic usage metrics would need to be tracked. CM will need to consider the various “data modes” that any associated software would need to track.

Maintenance and Servicing

As elaborated previously, routine maintenance activities may involve replacing or upgrading some parts. This would need CM to track the various subsystems involved in a particular major system version and which subsystem versions mesh with a general system version, so that if components are being upgraded that are not compatible with the current version the major system may be upgraded to meet those demands.

Information Management

Data management is a very essential part of the process as it involves sensitive medical data of patients. There are 4 potential obstacles to overcome for this framework:

Patient Data Collection

As more and more users and hospitals take part in this program, a common data collection metric must be developed so that the process remains element-agnostic, i.e., a patient that has undergone the data collection needed for a prosthetic at one hospital must be able to go to another hospital and pick up from there without having to go through the process again (or have minimal repeated processes).

Manufacturing – Healthcare Handshaking

Post the collection of data, the interpretations arising from the raw dataset would influence the activities of the medical professional and manufacturer respectively. This step involves abstraction of inner medical details away so that only the dimensions of the device are expressed. This is also resolvable using the same previous concept of a common data format that must be developed in collaboration with stakeholders so that there is proper transmission of intent between the two.

Field Data Transmission

While the benefits of having field data have been elaborated before, this assumes that there are methods for this data to be transferred to a repository accessible by stakeholders. This process can be blended with the same approach used for the patient data collection in that data can be collected locally by the device when in use and then transferred securely to a transfer point or an app that syncs with the database and the device, instead of having to do everything in real-time.

Privacy and Security

Security and confidentiality of patient’s data is of paramount importance, especially when there are laws in place to protect against the divulging of personal data of such vulnerable nature to the public domain. Having physical points of data collection and transfer is the best method to reduce the number of outlets data can leak from, and this paired with a robust cybersecurity protocol will protect data better.

Measurement

Having quantified metrics for tracking system execution throughout development is essential to make sure that everything is up to spec, especially in the medical field which is very data-driven and enforces almost negligible margins of error in reliability and performance. Thus, keeping tabs on all data brings confidence to stakeholders involved in the veracity of outputs of all the ensuing systems. In line with the MOEs and MOPs listed previously, the following methods may be applied to measure TPMs that dictate benchmarks:

| MOE | MOP | TPM | KPP | Benchmark | Method |

| Comfortable Usage > 8h | Weight | Mass | Maximum Weight Limit | < 10% var. | Weighing |

| Battery Life | Voltage/ Power | Minimum Battery Capacity | > 800Wh | Stress Testing | |

| Time | Minimum Operational Time | > 8h | Endurance |

Quality Assurance

Quality Assurance provides confidence to stakeholders during the development process that defects are being minimized and that sufficient measurement and other technical management processes are being employed to uphold the quality of the process. There are 4 possible quality assurance activities that can be performed:

Medical Compliance Policies

This is the most important and straightforward one, as following the established standards for the development of prosthetics (medical devices by nature) automatically accounts for a lot of the minor details that can be glossed over in this overview.

Periodic Reviews

Having reviews during the therapy sessions and during the manufacturing process keeps everyone informed of the current status of the system and helps weed out any potential deviations from the initial plans that can be discussed and mitigated on the spot.

Configuration and Information Documentation

As elaborated in the CM and IM processes, having documentation and reports that cover the essential aspects of the current system (compliance to medical policy as well as maximization of repeatable components) will blend with the periodic review process and these will serve as essential reference for historical knowledge and for future iterations.

Emergency Protocols

Keeping the user informed of what to do in emergency situations (if the prosthetic breaks during use or any other accident occurs) will keep the user safe and prevent untoward injury in such situations, while also providing other stakeholders with steps to follow for quick damage control.

Risk Management

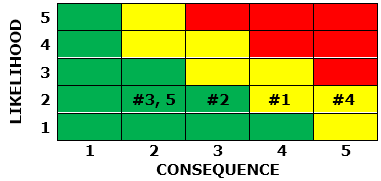

Conducting the risk management process is very important for medical devices in general due to the sensitive nature of their application, and prosthetics are no different. Some potential risks that could arise during development and usage of the system are listed using the “if x then y” framing below:

- If incorrect dimensions are taken then the design will be incorrect

- If the prosthetic is not medically compliant then the prosthetic will need to be redesigned

- If the prosthetic is difficult to use then user experience will be affected

- If the prosthetic breaks during use then the user will suffer injury

- If field data is not transmitted then future development will lack background data

These risks have been visualized using the risk matrix below:

From the above list, the following steps could be taken to mitigate the risks:

- Have more than one medical professional record data for second-opinion fallbacks and crosschecking information

- Employ SE processes to ensure strict adherence to medical compliance requirements, with fallback plans for quick iterations

- Tighten requirements and measurements to better define margins of error and acceptable metrics

- Train the user on acceptable methods of usage for the prosthetic to prevent improper usage, and include factors of safety in the design to prevent any accidental loads

- Have the user either check in with their medical professional regularly or design an application or similar element to record data from the device and transmit it elsewhere

The projected revised risk matrix after mitigation is shown below.

References

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Mar;89(3):422-9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005. PMID: 18295618. ↩︎

- Tirrell AR, Kim KG, Rashid W, Attinger CE, Fan KL, Evans KK. Patient-reported Outcome Measures following Traumatic Lower Extremity Amputation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021 Nov 11;9(11):e3920. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003920. PMID: 35028257; PMCID: PMC8751770. ↩︎

- Witt, John Fabian, Workmen’s Compensation and the Logics of Social Insurance (April 2002). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=311582 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.311582 ↩︎

- Riel LP, Adam-Côté J, Daviault S, Salois C, Laplante-Laberge J, Plante JS. Design and development of a new right arm prosthetic kit for a racing cyclist. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2009 Sep;33(3):284-91. doi: 10.1080/03093640903045198. PMID: 19658017. ↩︎

- Zidarov D, Swaine B, Gauthier-Gagnon C. Life habits and prosthetic profile of persons with lower-limb amputation during rehabilitation and at 3-month follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Nov;90(11):1953-9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.011. PMID: 19887223. ↩︎

- Kahle JT, Klenow TD, Highsmith MJ. COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF AN ADJUSTABLE TRANSFEMORAL PROSTHETIC INTERFACE ACCOMMODATING VOLUME FLUCTUATION: CASE STUDY. Technol Innov. 2016 Sep;18(2-3):175-183. doi: 10.21300/18.2-3.2016.175. PMID: 28066526; PMCID: PMC5218538. ↩︎

- MacKenzie EJ, Jones AS, Bosse MJ, Castillo RC, Pollak AN, Webb LX, Swiontkowski MF, Kellam JF, Smith DG, Sanders RW, Jones AL, Starr AJ, McAndrew MP, Patterson BM, Burgess AR. Health-care costs associated with amputation or reconstruction of a limb-threatening injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Aug;89(8):1685-92. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01350. PMID: 17671005. ↩︎

Leave a comment