Humans are not disabled. A person can never be broken. Our built environment, our technologies, are broken and disabled. We the people need not accept our limitations, but can transcend disability through technological innovation.

Hugh Herr

Human Hands and Embodied Intelligence

Humans, aside from their advanced intelligence, also hold several physical advantages over other terrestrials, bipedal walking and the opposable thumb being chief among them. The ability to interact with and dexterously manipulate objects in the environment, one of the most important physical abilities we have, forms a core part of the human experience. It allows us to engage in a wide range of activities, from cooking and writing to performing surgeries and playing instruments, blending fine motor control with precise tactile feedback. The experience when manipulating objects provide a direct connection to our environment, enhancing our understanding and interaction with the world around us.

Thus, when we lose a hand or leg to injury or disease, restoring what was once lost to us has formed the primary motivation behind the development of artificial limbs, which have helped amputees and those born without limbs. However, while current prosthetic devices have been successful in restoring a majority of motor functions necessary for users to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), they do so at the cost of increased complexity due to the need to compress intricate mechanisms within a small volume. This, in turn, increases manufacturing difficulty, which finally increases overall costs. The lack of advanced sensors that may be integrated within the materials or mechanisms making up the prosthesis―essential for providing effective sensory feedback about the environment in contact with the device to the user―further complicates the technical problem. This Size, Weight, Power, and Cost constraint (SWaP-C) surrounding the design and development of prosthetics thus make devising solutions an active, albeit difficult, area of research. This is where Soft Robotics comes in.

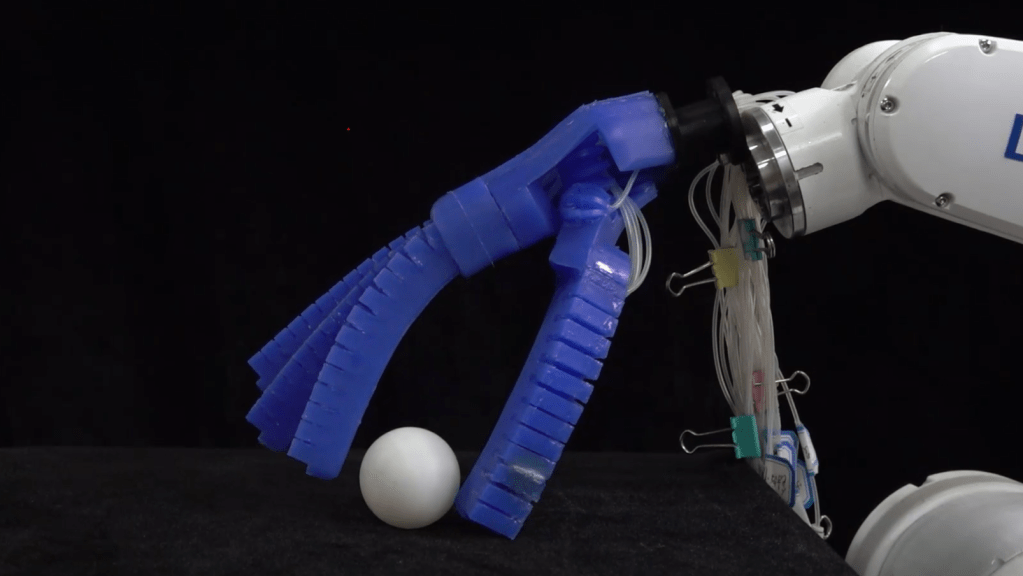

The BlueHand, a soft anthropomorphic robot gripper modelled from pneumatically actuated silicone fingers, grasping a ball.

D. Mei et al., “Blue Hand: A Novel Type of Soft Anthropomorphic Hand Based on Pneumatic Series-Parallel Mechanism,” in IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 7615-7622, Nov. 2023, doi: 10.1109/LRA.2023.3320906.

Soft robotics, an emergent branch of robotics defined by the use of silicone, plastic, and other non-metallic polymer-based materials, has shown great promise in mimicking biological organisms and structures in form as well as function. A potential soft robotic prosthetic hand made of silicone, for example, would be able to not only conform to the form factor of human limbs by design but, more importantly, also contain embeddable sensors within the silicone matrix. Including these sensors can enable the prosthesis to communicate more information about the environment to the user, and the embeddability improves the ‘design density’ of the product, allowing for better space utilization.

That being said, a variety of novel soft sensors using easy-to-apply methodologies such as the magnetic Hall effect or electrical impedance exist in the literature; however, translating them into an anthropomorphic context remains an active area of research. While quite small—one of the smallest soft magnetic sensors in the literature is about the size of a grape—soft sensors require complex electrical setups and fabrication techniques. Most sensors are also designed from scratch to be included on robots, without considering how to optimize the design such that the sensor could be included more generally in any application, not just a bespoke installation on a soft robot.

My current research in soft sensors for anthropomorphic hands seeks to optimize the design of existing soft sensing solutions, focussing specifically on how existing sensors used in soft robots as well as those developed in isolation can be redesigned to be more adaptable to prosthetic function and the human form. This may potentially open new avenues for exploring principles and technologies traditionally seen in soft robotics applications, such as the ones described previously. Prosthetics and bionics, historically a bastion of medical literature, may also find a breath of fresh air with the inclusion of work from different fields of engineering, ushering in interdisciplinary research between the two often disparate sectors. If not soft sensors, perhaps intelligent materials, multi-material manufacturing, or printable electronics may find themselves to be fitting solutions to technical issues plaguing current prosthetics research.

Recent Articles:

Soft Robotic Prostheses: Exploring Present Trends and Broader Impacts

Recent innovations in active prosthetics have significantly improved the rehabilitation of amputees into normal society, increasing the capability of performing activities of daily living (ADL). However, the inherent limitations of traditional prostheses call for the adoption of soft robotic technologies to better bridge the biomimetic gap towards natural human anatomy. This review examines ongoing research…

Low-Cost, Sustainable Solutions for Amputees with a 3D-Printed Integrated Prosthetic System

This article discusses the application of systems engineering principles to the design and development of prosthetics, emphasizing collaboration among stakeholders in medicine, manufacturing, and amputee communities. With an increasing number of amputations due to medical conditions and accidents, the need for affordable and effective prosthetic solutions is critical. The proposed system seeks to streamline the…