Conventional mobile robots or ‘rovers’ for uneven terrain often rely on complex linkages for obstacle traversal, which can hinder performance. Soft robotic materials and mechanisms are thus an elegant solution owing to the inherent compliance of soft materials. This project outlines the development of a ‘soft rover’ for the 2024 inter-university soft robot competition, integrating traditional rover designs with soft robotic materials. We discuss competition specifics, design considerations, mechanical and electronic aspects of the rover, and insights into its performance challenges and innovative behaviours observed during development.

Thanks to Samruddhi Jadhav and Jessica M. Rhodes for working with me on this project!

Mobile robots are one of the largest applications of robotics today, playing a crucial role in various sectors including agriculture, exploration, and logistics. With the ability to navigate autonomously in an environment, much research has been done to make mobile robots more efficient in their tasks, allowing them to perform jobs that were once exclusively human-operated. However, such optimizations are mostly in software, which can do little to assist the robot in navigating uneven terrain — there is no point in having an advanced navigation algorithm if the robot itself can’t even drive over an obstacle. Thus, mobile field robotics serves to augment existing mobile robot technology with more robust mechanical assemblies to allow the robot to traverse harsh environments effectively. Due to the uncertainty of such environments, various buggy/rover concepts derived from strategies used for off-road vehicles have been adapted to fit the purview of a typical mobile robot. This allows it to survive harsh mechanical loads, while the software and electronics provide the intelligence needed to plan a path through cluttered sections.

Rovers and buggies have found use most in the realm of space robotics, such as the NASA Mars Rovers1, which have revolutionized our understanding of extraterrestrial terrain. Most solutions follow similar design principles to traditional mobile robots, with a central chassis housing electronic components and wheels for the mobile robot to move around. However, the primary difference between rovers and normal mobile robots is the presence of an adaptive suspension that allows the wheels to adapt to rocks and ditches, enabling the robot to stay stable regardless of the obstacles in its path. This comes at the cost of introducing more complex mechanisms and rigid assemblies, as most typical rover suspensions use a rocker-bogey mechanism, a rigid linkage mechanism that can handle diverse terrains. Recent advances in rover design, however, have hinted at the potential for incorporating the principles of soft robotics and soft materials in the design and development of these rovers2. One of the main advantages of soft robotics is the wide use of soft, compliant materials which allow for high elastic deformation under load; this can allow a mechanism to have inherent ‘suspension’ built into it because of being made from such materials, thus improving overall flexibility and adaptability in rugged terrains.

With this in mind, we set out to combine traditional rover design with soft robotic principles by developing a soft compliant rover, using silicone wheels and a chassis made of TPU. Together, they can provide enhanced performance in a variety of challenging environments. Throughout the course of designing this rover, we came across interesting behaviours of the whole assembly, such as unexpected interactions between components and variations in wheel performance on different surfaces. We faced various challenges during the fabrication and assembly process, particularly in achieving the perfect balance between rigidity and flexibility, which is essential for navigating the unpredictable landscapes this rover would encounter. These insights and challenges will be elaborated on in ensuing sections, as we explore the implications of our work in both theoretical and practical applications for future mobile robotic systems.

Competition Description

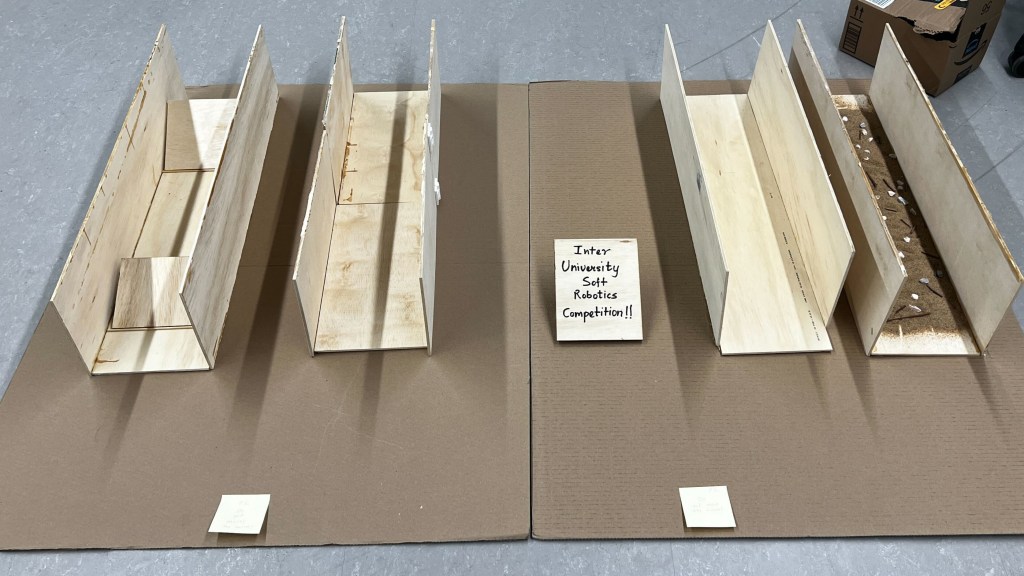

The Inter-university Soft Robot Competition held between WPI, UMich and BU entailed a 15-minute window per team to tackle a series of mobility challenges within this time frame, with the opportunity to attempt these challenges multiple times. The mobility challenges are strategically set within a variety of tunnel environments, each designed to test different aspects of the robots’ operational capabilities:

- Simple Flat Tunnel: This tunnel presents a clear path without obstacles, focusing purely on the robot’s ability to navigate straightforward terrain effectively.

- Incline: This segment challenges robots with an incline that both rises and falls, requiring them to effectively manage transitions across two varying slopes. This test is crucial for assessing the robots’ ability to handle changes in elevation while maintaining stability and control.

- Granular Media: In this challenge, robots will navigate through a tunnel filled with sand, which tests their ability to manoeuvre over unstable and shifting substrates. This is a critical test of the robots’ adaptability and traction on less predictable surfaces.

- Curved Path: This part of the competition involves a tunnel that features adjustable angles, putting the robots’ manoeuvrability to the test. The challenge not only assesses the robots’ ability to navigate turns but also adds a strategic element as teams have two opportunities to select the angle of the curve, allowing them to demonstrate advanced planning and adaptability.

Each of these challenges is designed to push the limits of robotic design and functionality, ensuring that only the most versatile and robust robots excel. The diverse conditions presented in these tunnels mirror real-world scenarios, preparing the robots for practical applications beyond the competition. Based on these challenges provided, we decided to analyse each section to find the best strategy for each, and ultimately decided on a ‘car’-oriented design.

Design Principles

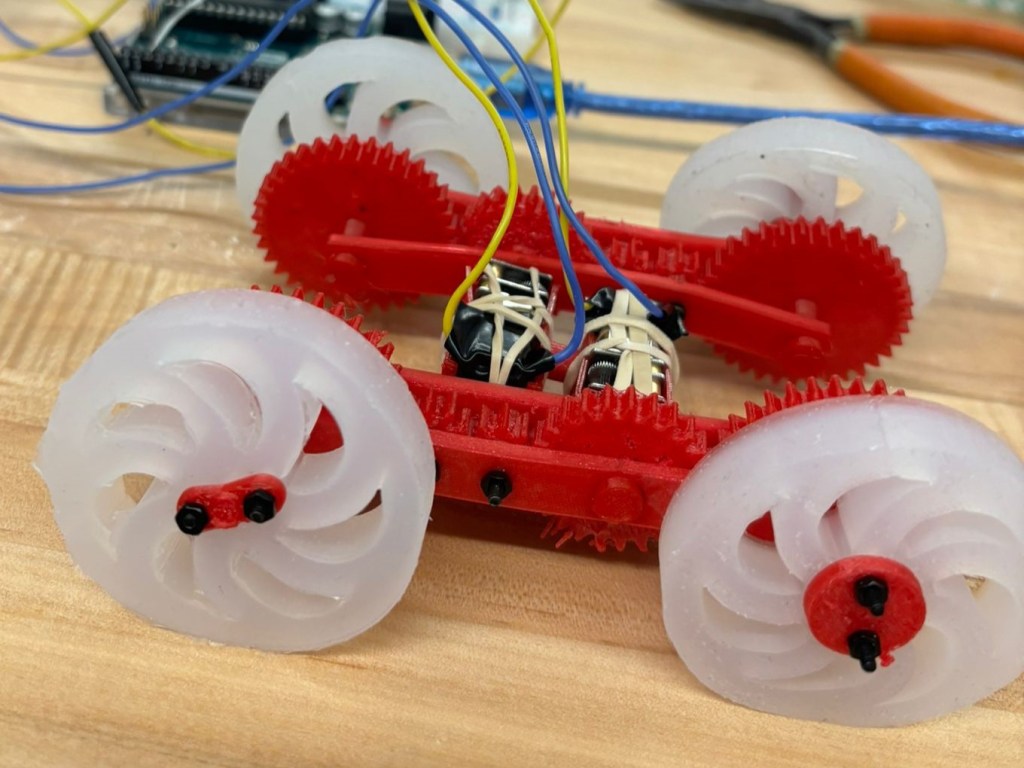

Given the competition analysis, in the design of our small rover-like soft robot, we adhered to several core principles that guided our choices from conception through to realization. Our primary goal was functionality and adaptability, enabling the robot to efficiently navigate diverse terrains and obstacles as specified in competition guidelines. To achieve this, the design of the rover was split into the following sections:

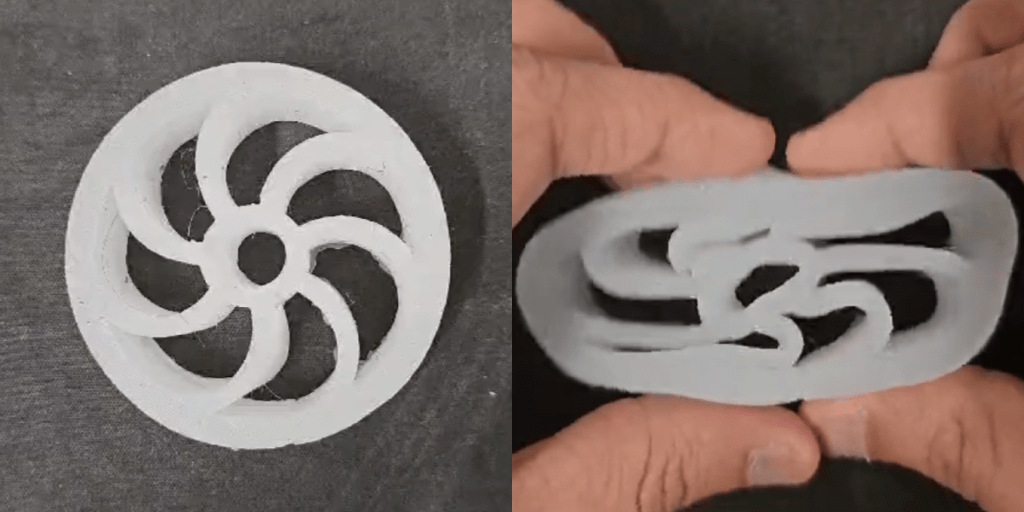

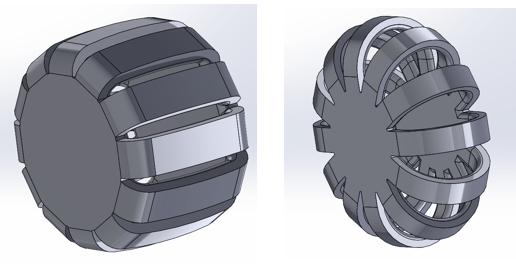

Spiral Wheels

Inspired from the concept of airless tires3, we incorporated silicone wheels made of Ecoflex-0030 into the design, depicted in Fig.~\ref{fig:wheel}. These wheels provided the necessary traction and flexibility required for varied surfaces, including sand and inclined planes. The principle behind using angled spokes is rooted in the need to manage how the wheels deform when subjected to external forces. By angling the spokes, the wheels can flex in a controlled manner, absorbing impacts more effectively and adapting to surface irregularities without compromising structural integrity. This controlled deformation is critical in maintaining consistent contact with the ground, thereby improving traction and stability. Moreover, the deformation characteristics introduced by the angled spokes help in distributing the stresses more evenly across the wheel structure. This distribution is vital for preventing localized stress concentrations, which could lead to premature failure of the wheel material, especially under the harsh conditions of a competition. The ability of the wheels to deform and return to their original shape efficiently also aids in preserving the motor’s energy, contributing to better energy management and prolongation of the robot’s operational time.

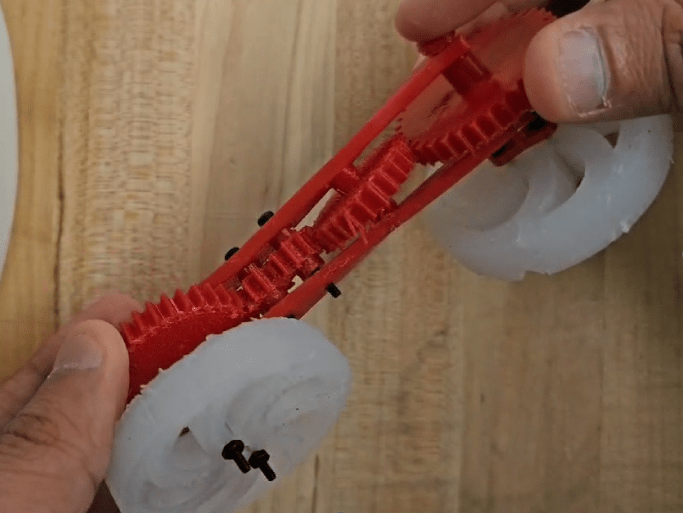

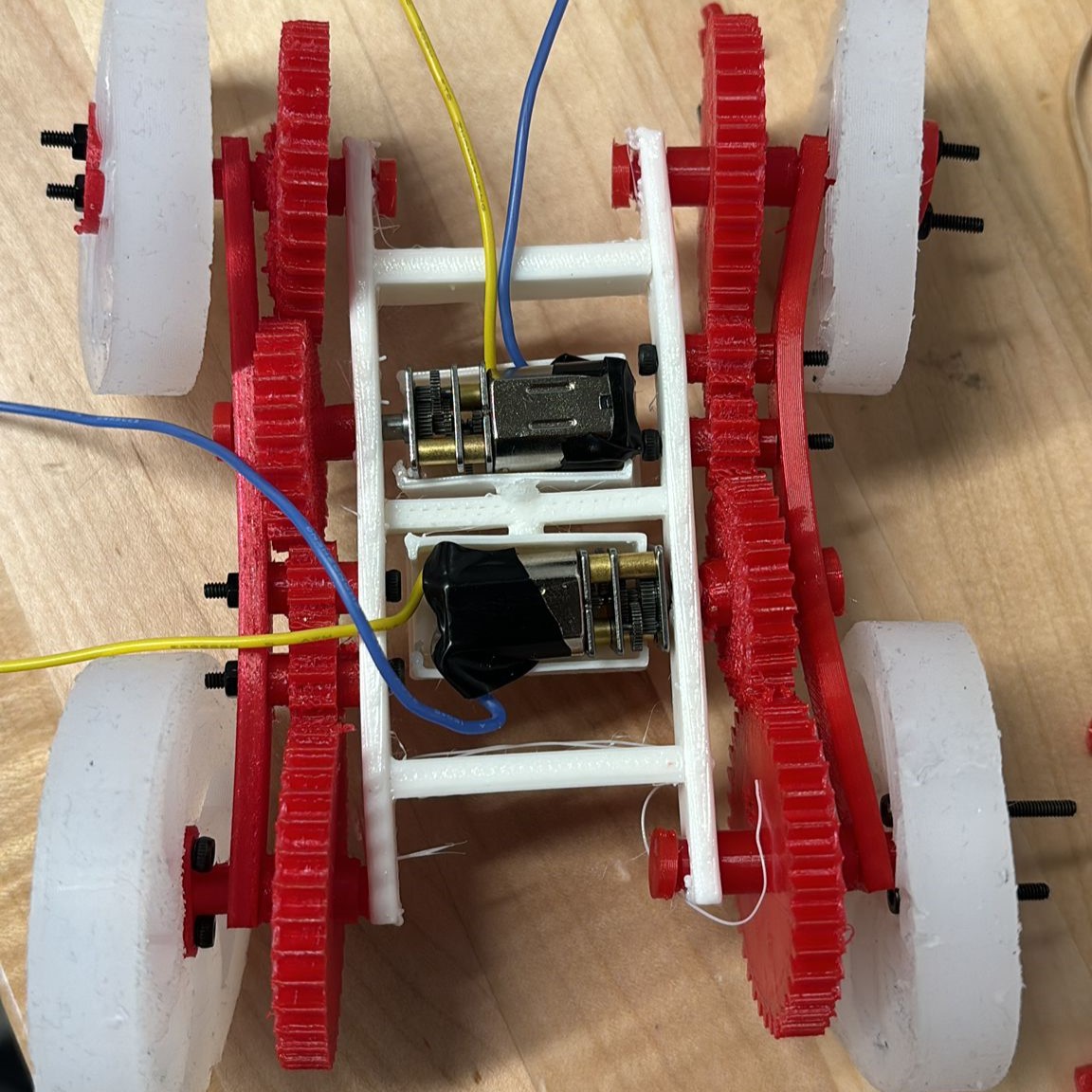

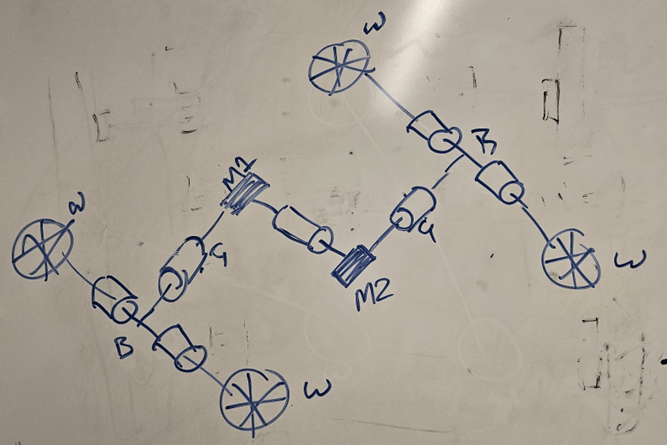

Soft Geartrain

Silicone wheels, while providing superior traction and adaptability on soft or uneven surfaces such as sand or gravel, inherently possess a high frictional coefficient, which can greatly influence the performance of robotic systems. While beneficial for grip and stability, this necessitates a higher torque to overcome the increased resistance during movement, especially when initiating motion or traversing steep inclines, where the demand for power becomes even more pronounced. The selected gear ratio of 1.4 was strategically chosen to reduce the robot’s revolutions per minute (RPM) while simultaneously increasing its torque, facilitating an optimal balance between speed and control. The robot thus maintains stability and control while preventing the wheels from digging into soft substrates, which could result in the robot becoming stuck or excessively draining battery power due to continuous high-load conditions, hindering its operational efficiency. The enhanced torque ensures that the robot can apply sufficient force to move forward effectively without excessive wheel slip, which would compromise navigation accuracy and efficiency, particularly in dynamic environments where precise manoeuvring is essential.

Although gears were the preferred option compared to pulleys and timing belts due to their high torque output, reliability, and greater efficiency in power transmission, we wished to ensure that the entire mechanism was designed to excel under competition conditions. Therefore, we utilized 95A TPU, a 3D printing filament that results in soft, compliant print bodies. This decision was made to keep the whole mechanism as soft and adaptable as possible, effectively addressing the unique and varying requirements of the competition. By implementing this material choice, the mechanism not only became lightweight but also compliant, allowing for dynamic responses to the terrain. This flexibility had the remarkable effect of enabling the entire gear train to twist and conform as needed, ensuring the robot could seamlessly navigate complex obstacles without sacrificing performance or risking damage to its components.

Electronics and Control Scheme

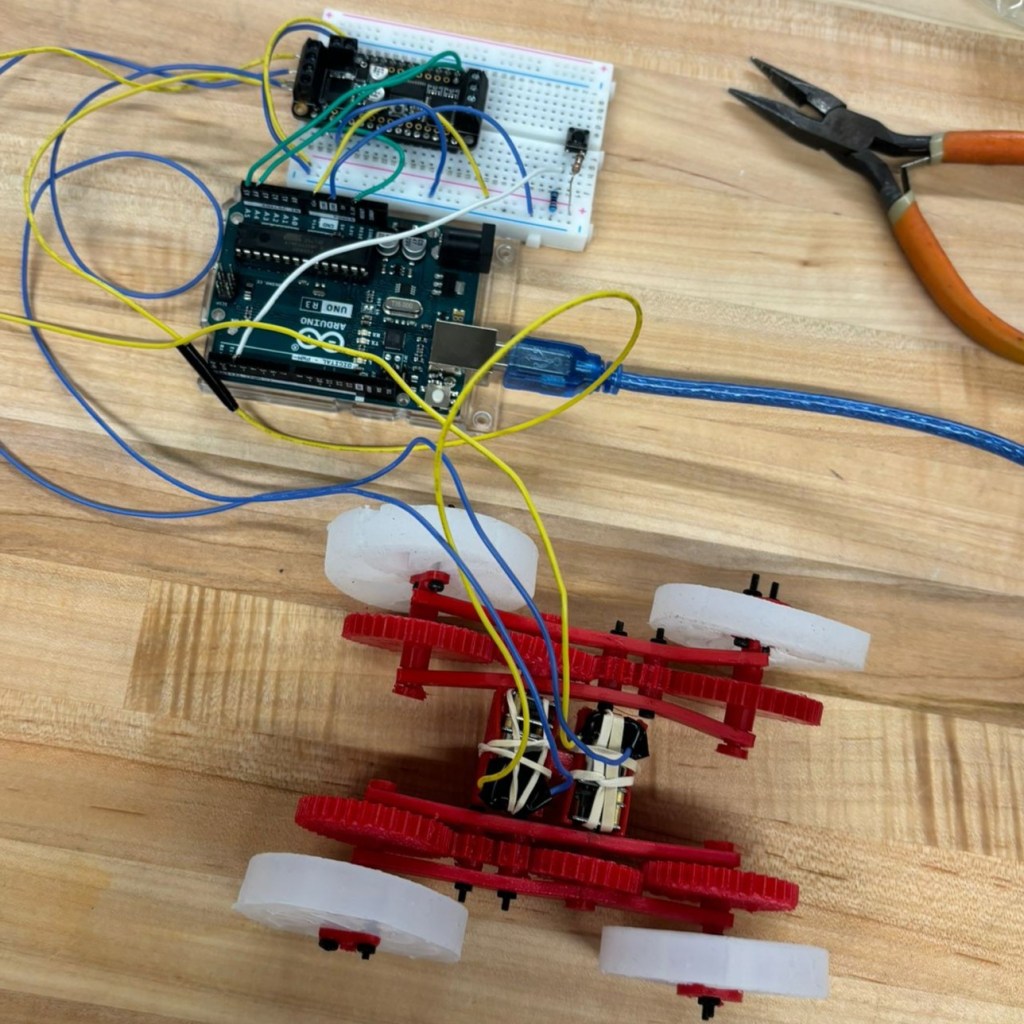

Initially, we had elected to use a wireless control scheme similar to the setup deployed on the Salamander / Lizard projects in the lab, this entailed an Adafruit Stepper in combination with the DC Motor FeatherWing. We planned on using two separate buttons, one to turn each side of the motors on and off, controlling the steering of the device.

Unfortunately, we faced some Arduino based errors and decided with the time crunch of competition day arriving soon. So we stripped down on our electronics to the bare necessities. The final electronics consisted of two simple buttons manually controlling power to each motor. This design allowed for the steering control that we wanted but took away our ability to properly control the motors and ensure simultaneous and evenly powered motors.

Conclusion and Future Work

This report described the design and development of a soft compliant rover combining traditional rover design with the principles of soft robotics. Various ideas were explored to try to incorporate soft materials and compliant mechanisms in the design of the rover. We were successful with designing the rover, but due to challenges faced during fabrication and assembly we had limited success in testing and final deployment. As of now, further work would entail further streamlining the fabrication process to ensure a more optimized assembly, and making the robot tetherless. This would entail redesigning the central section of the chassis so that we may also make it waterproof (or water resistant) so that we can fit electronics inside the chassis without letting it be damaged by external fluids. Furthermore, we would also wish to improve upon the design of the wheels, working on potential ‘inflatable wheels’ that could be actively adapted to the terrain as opposed to the current passively adapted spiral wheels4.

Having explored this concept, we feel that this opens up the possibility for further research that combines space technology and soft robotics in applications aside from inflatable habitats and wearables, demonstrating the potential for the application of mobile soft robotics for exploration in space and extraterrestrial environments. There might also be some potential area for exploring interpretations of typically rigid mechanisms through a soft material / robotic lens, such as Osawa et. al.’s work designing gears from gummies5. These intersections of soft robotics with different fields can have strong broader impacts on other fields as well, as they become more open to cross-discplinary group work.

Gallery

References

- “Perseverance Rover Components – NASA Science.” [Online]. Available: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/mars-2020-perseverance/rover-components/ ↩︎

- M. D. Lichter, V. A. Sujan, and S. Dubowsky, “Experimental Demonstrations of a New Design Paradigm in Space Robotics,” in Experimental Robotics VII, D. Rus and S. Singh, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2001, pp. 219–228. ↩︎

- N. O. Nikolov and P. Siegfried, “Michelin Uptis – Are airless tires the future of the automotive industry?” Automobile Transport, no. 52, pp. 98–107, Jul. 2023. [Online]. Available: http://at.khadi.kharkov.ua/article/view/282658 ↩︎

- C. Zheng, S. Sane, K. Lee, V. Kalyanram, and K. Lee, “α-waltr: Adaptive wheel-and-leg transformable robot for versatile multiterrain locomotion,” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 941–958, 2023. ↩︎

- K. Osawa, K. Duan, and E. Tanaka, “Development of Soft Gears Made of Edible Gummies for Self-propelled Endoluminal Robot,” in Advances in Mechanism and Machine Science, M. Okada, Ed. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023, pp. 163–172. ↩︎

Leave a comment